|

Trip to Cameroon, 20-30 September, 2006 |

| African rationality, Bamileke royal establishments, hypothetical Sunda expansion, and the ongoing supervision of Cameroonian PhD students |

return to Topicalities page | return to Shikanda portal

On the strength of the excellent relationships that were established with Cameroonian colleagues and institutions when Wim van Binsbergen visited that country for the first time in 2005 (click for details), he was invited as External Examiner and President of the Jury in the context of the public defense of Jean Bertrand Amougou's thesis: 'La rationalité chez Hebga: Hermeneutique et dialectique', completed under the supervision of Professor Ondoua of the Department of Philosophy, Faculty of Humanities, University Yaounde I. The thesis proved an interesting and innovative piece of work. Tracing the eclectic and protacted itinerary of the Cameroonian thinker, social scientist and Roman Catholic priest Meinrad Hebga (*1931), and discussing how the latter has positioned himself vis-à-vis the time-honoured theme of rationality as the hallmark of the human being and a fortiori of the philosopher, M. Amougou has managed to address central issues in the construction and deconstruction of an African rationality. Following in Hebga's footsteps, and seldom incisively critical, Amougou's exploration of rationality ranged from the Presocratics to Habermas, and, beyond philosophy in the narrower sense, explored the relevance, from a consideration of African rationality, of recent Afrocentrist throught; Amougou also expertly ventured into the twentieth-century scientific thought of Teilhard de Chardin, Prigogine, and Morin, as well as into the reconsideration of paranormal phenomena in the African context. The thesis, on which I hope to report more extensively in a more specialised venue, certainly reflected the resilience and resourcefulness of current philosophy in Cameroon and in Africa as a whole, addressing topics of unmistakable African relevance and topicality -- despite large gaps in the bibliography (reflecting the paucity of local resources), and vast unexplored tracks of modern thought: most conspicuously: poststructuralist French philosophy which throws a totally different light on rationality; and Mudimbe, by comparison to whom Hebga's trajectory (between African specificity and world-religion universalism) would look familiar but rather less inspired, as another case of clerical intellectualism in 'the liberation of African difference' (Mudimbe).

After an exhausting five hours of presiding over the soutenance, I had only one hour to recover over food and drinks, after which my second marathon task of that day had to be discharged: my three-hour seminar on 'Possibilities and impossibilities of African science', with my long-standing friend the epistemologist and ethician Professor Godfrey Tangwa in the chair. In the blissful philosophical reserve of the Department of Philosophy, Yaounde-I, unscorched, so far, by the hot wind of Derridean post-structuralism, feminism, ethnophilosophy, or by other similar assaults on the Aristotelian logical tradition of the excluded third, it was at first only the conjunction embedded in my title that gave rise to puzzlement and protest. However, when I went on to propose

that my personal, prolonged and (I suppose) profound experiences with 'sangoma necromancy' (Tangwa) might pass as an indication that 'African science' could be a viable concept,

and that such 'science' might well be able to produce valid and reliable specialist knowledge at a par with, parallel to, and not necessarily inferior to, North Atlantic i.e. 'global' science (also cf. van Binsbergen, Intercultural Encounters, 2003, ch. 7, pp. 235-297, where this claim is argued in detail),

then even the sophistication and knowledge-political awareness of Sandra Harding (locally an unknown and uninvited guest; cf. van Binsbergen 2002 and in press) could hardly save me from contempt and ridicule -- had it not been for the authority invested in my earlier that day as Monsieur le Professeur, Président du Jury. However, as the discussion developed into over one hour and a half, and waxed more and more animated and general, it became manifest that the audience did not remain totally deaf to my plea for a post-Popperian and post-hegemonic epistemology. Such an epistemology, I claimed, could be grounded, in part,

in African experiences

that, meanwhile, could be recognised as regional manifestations of experiences which (even though uncaptured and unrecognised by North Atlantic, 'Scepticist' science) were shared by many other humans however wide apart in space and in time.

Thus the audience gradually appeared to become prepared -- largely on its own initiative! -- to take in its stride the idea of essential continuity between divination systems such as Chinese I Ching, Arabian cilm al-raml, West African Ifa, sangoma hakata divination, and Malagasy sikidy -- a topic on which I have published extensively. And having claimed the essentially language-based and specialist nature of science (beyond the conceptually and ontologically empty claim to the effect that sicnce is first and foremost 'a method'), we discussed at comfortable length

the relatively recent emergence of science (Ancient Near East, just over 5,000 years ago -- as part of a Neolithic package further comprising writing, the state, and organised religion)

as against the much longer history of human language: e.g., with already a fairly reliable prehistorical reconstruction of the '*Borean' language, as a putative mother form from which language (macro-)families as diverse as Indo-European, Niger-Congo, Dene-Sino-Caucasian and Austric may be claimed to have sprung, to be situated at about 25,000 Before Present, while the original, primal 'Mother Tongue' was undoubtedly even much older.

Thus regurgitating a number of themes of my philosophical and comparative historical research of the last few years, the seminar rather than exhausting me, restored my vital forces, and reassured me that my long period of illness had effectively come to an end. At the time my argument remained a rambling, impressionistic and impetuous undertaking, but soon I had occasion to cover much the same ground in a paper on 'Connections in African knowledge' (Leiden 2006), a text which greatly benefitted from the Yaounde I discussion.

The Amougou defense created a welcome context for further on-the-spot supervision of two African PhD students, Mssrs Pius Mosima and Pascal Touoyem, whose work is making good progress. Belonging to widely different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds in Cameroon, their collaboration within the wider supervision structure (which includes close interaction with one another and occasional visits to one another rural homes) is a field experiment in the interculturality (cf. van Binsbergen 2003a) that is as central to their projects as it is to their supervisor's.

The supervision structure amounts to a viable and enthusiastic local logistic base, which allowed me (even on my first intercontinental trip after long and serious illness) to venture far outside the capital, and specifically to establish first-hand acquaintance with a number of the Bamileke / Grassfield kingdoms (especially Bandjoun, Baham and Bamum). In these three capitals, the royal museums / treasuries were thoroughly inspected, relevant documentation collected, and promising links were established with the curators, who turned out to be well-qualified and prolific specialists in their fields. I was greatly impressed with the interviews granted to me by the curators of especially the royal treasuries / museums of Baham and Bandjoun, and I hope to be able to come and tap their vast knowledge and insight on future occasions. I was especially honoured by the personal audience that was granted to me by His Majesty King Pouaham Max II at Baham. Beyond the neo-traditional, nostalgic construction and reconstruction (in which, especially at Bamum, the hand of an antiquated museological and ethnographic North Atlantic tradition can often be felt -- as well as the hand of the lucrative African arts trade), the Grassfields offer, of course, the richest and most vital African manifestations of a royal court culture which, albeit with many transformations and innovations, extends from the northwestern edge of the Bantu-speaking realm all the way to Southern and Eastern Africa. On the basis of my research, over the decades, into Zambian kingships (van Binsbergen 1981 and 1992 etc.) (gradually shading over into personal participation and involvement as an adopted royal), and of my comparative and theoretical work on African kings in precolonial and postcolonial settings (van Binsbergen 2003b) I could apppreciate the Grassfield situation as eminently inspiring and illuminating for African kingship (and resilient traditional leadership) as a whole. Meanwhile the Grassfields situation also makes me look at certain details from Zambia in a different light, as will be clear below. I am grateful to my students and their associates for affording me this far too short but effective glimpse into one of the greatest traditions of African cultural achievement. The present visit thus nicely complements my 2005 experience, equally illuminating and pleasurable, with Bakwerri segmentary social structures around Mt Cameroon and Buea. It was exciting to spot, in the Grassfields, not only continuities with so many themes with which Zambian kingship had made me familiar for decades, but also some of the more recent themes in my comparative work, such as

the abundance of leopard motifs (one royal establishment even displayed elaborate paintings of leopards and lion combine, as if the mythical complex I have called 'the cosmology of the lion and the leopard' was still a viable reality here!)

the abundance of spider themes -- now atenuated so as to become a symbol of zealous human work, but (as its use in divination, cosmogonic and state legitimation still indicates, often in the presence of other symbols of the primal and cosmogonic divinity) originally as an evocation of a maternal cosmogonic deity associated with weaving, initiation and often also warfare -- incidentally, an entity which may also be invoked, in the Grassfields and elsewhere in West Africa and far beyond, in the Janus-like combination of beginning and end (see illustrations below)

and, beyond the man-made beauty and decay of royal establishments with their 'architecture of power', and fertilising these man-made places with their eternal non-human sacrality, there are the eminently primal, wild places that, throughout Bantu-speaking Africa, indicate sites of cosmogony (where the Earth reputedly opened to as to give forth the first animals, plants and humans -- or where, in a later mythical dispensation, such beginnings of earthly life arrived suspended from a cord, thong or ladder, from the sky). This endows these spots of nature with great cultic, initiatory and royal legitimation. The spots in question are waterfalls, and strange rock formations that, despite their megalithic reminiscences, appear to be far too large (involving boulders of 100 m and over) to be due to human action. Significantly, the Baham curator spent what little time was available, long after the museum's closing hours, not on a round through the collection that had been entrusted to him, but on showing us a video on which a local Christian church is taking re-possession of the ancient nature shrine of Fovu' -- renowned for its healing powers since times immemorial. Recognisable Church songs mixed with ancient historical African songs in local languages, the man-made boundary between imported world religion and traditional African religion faded away in the face of the sacred, and the sacred place looked remarkably like an Upper Palaeolithic initiation site in Europe's famous Franco-Cantabrian region, or an Australian aboriginal site. It must be another sign of resilience that in the outside world, the name Fovu is primarily known as... that of Baham's eminently successful football team.

At the back of my mind there was another reason to be interested in the Grassfields. In a bid to define Africa's contribution to global cultural history more fully and more convincingly, I have been engrossed, the last few years, in long-range historical and cultural reconstruction, largely on the basis of comparative mythology, but with important contributions from linguistics, archaeology and genetics (van Binsbergen 2005 and 2006). Especially the very extensive mythical and genetic material nowavailable gave me reason to take up once more the old theme (cf. Hornell 1934; Jones 1964; Dick-Read 2004) of Indonesian influences upon Africa, especially in the light of the Sunda expansion hypothesis (Oppenheimer 1998).

Having detected -- to a point of satisfying my own, usually quite demanding, methodological taste -- a considerable number of Sunda themes in the part of Africa (west Central Zambia: Nkoya, Mashasha and Ila peoples) that I have known from personal intensive historical and ethnographic fieldwork, linguistic competence and social participation since the early 1970s,

and having begun to re-read my far less extensive ethnographic and historical data on the Manjaks of Guinea Bissau in a potentially Sunda light,

I was now interested to sound for possibly Sunda ethnographic elements in West Cameroon -- an area that, in the light of my mythological and genetic data, would also seem to have undergone considerable Sunda influence in past millennia. Considering that such influence would derive from what I postulate to have been a transcontinental nautical network that first emerged before the outrigger was invented and before Madagascar was colonised from Indonesia, and that may have had some formative influence on the Indus valley and the Persian Gulf, we find ourselves, as far as Africa is concerned, in the formative phase of the Bantu linguistic group (I see reason to postulate some Sunda influence even on the formation of proto-Bantu -- although this is, like all of these long-range issues, a realm where angels fear to tread), so before effective Bantu expansion. Nonetheless, Sunda influence, if any, may have endured for several millennia, and once the transcontinental network was in place, the latter may have served (in ways favoured by Afrocentrists like Clyde A. Winter) to conduct west-east transcontinental cultural currents in addition to the Sunda current which was, of course, primarily east-west. At any rate, if any Sunda influence may be detected in the ethnographic material in addition to the genetic, linguistic and especially mythological indications, it would be very difficult to detect and isolate such influence now, from under layers and layers of later cultural local and regional dynamics as well as transregional influences, throughout about five millennia up to the present. Empirically, the whole idea of detectable Sunda influence on West Africa may have to be given up for lack of decisive data anyway (hence Dick-Read's title: Fanthom voyagers) -- although the authors mentioned above argue their cases with remarkable persuasiveness.

All considered, I am far from disappointed that my first venture into West Cameroon yielded only very meagre Sunda clues:

- a general version (A), where, conceptually, the Flood is simply the denial of the cosmological order that was established when, in cosmogony, land was separated from among the more primal water (up, aside, and below the land). This version appears to be associated with mtDNA Type B, and it arose, with the attending cosmology, when the subset of Anatomically Modern Humans characterised by such mtDNA arose in Northern Central Asia c. 25,000 Before Present. It is this general version that spread very widely, e.g. to the New World

- a very specific version (B) of Flood myth, which comes as an entire package comprising some original sin (often associated with sexuality and/or incest), a viable link between heaven and earth (bridge, ladder, tower), divine pre-warning of a selected, favoured human, an escape vessel, the flood itself, and subsequent re-establishment of a new link between heaven and earth (e.g. rainbow). This second type spread all over Oceania (again on the wings of mtDNA Type B expansion from Indonesia: the eastbound variant of Sunda expansion from c. 7,000 BP onwards), but also westward, to India (Mani), West Asia (Utnapishtim, Athrahasis, Ziusudra, Nuah), Africa especially the Atlantic coastal regions and the Mozambican/Angolan corridor, and the Mediterranean. This very specific and elaborate version of Flood myth is unmistakably Sunda, part of Sunda westbound expansion, and it has been identified as such by Oppenheimer (albeit not against the -- highly instructive, and relativising -- background of the general version (A) whose geographical and temporal scope is much more extensive).

Now, the identification of such flood myths in the Western Grassfields (Kahler-Meyer in Dundes 1988), as part of the Atlantic distribution of such myths in sub-Saharan Africa, is to me another sign of Sunda influence in the Bamileke area.

What does all these indications of Sunda influence mean? If they are to be taken seriously as facts, they certainly do not mean that Africans today are Asian, specifically Indonesians in disguise. Just like that fact that the remotest ancestors of all living human beings (of all Anatomically Modern Humans) emerged in Africa and exclusively lived in that continent between 200,000 and 80,000 or 60,000 years Before Present, does not mean that Indonesians, and all human beings today for that matter, should be considered Africans. The identitary and geopolitical labels that make for hot issues today, have no meaning when projected back into the past one or two millennia, or more. In the course of cultural history, cultural specificities arose (largely as regional specialisation and as the articulation of local and regional gene pools), and were subsequently diluted and annihilated, to be supplanted by other cultural specificities. Moreover, even if there are covert traces of Asian genes, somatically the people around the Bight of Benin are emphatically Africans, -- Africans who, apparently, have appropriated, transformed and innovated a selected package of SE Asian cultural traits. If we could demonstrate (as it appears we can) a substantial Indonesian influence in the Western Grassfields and elsewhere in Africa, that only points to some of the raw material out of which, in the course of millennia, African populations and regional cultures were shaped -- as specifically African. Demonstrable Indonesian influence does not mean that the historic cultural and artistic achievement of the people of the Western Grassfields, or of Africa at large, was less than it appears, or merely amounted to passively accepting and holding on to foreign models. The continuities noted here simply mean that Africa, just like other parts of the world, has been part of a global network of dynamic cultural exchanges, in which Africa now took the lead and contributed to other continents, now accepted innovations from elsewhere and reworked these to produce a localising transformation of them. Transcontinental cultural currents are a ubiquitous fact of cultural history, and they can be demonstrated in and for Africa just as for anywhere else.

Let us just remind ourselves how also the crucial elements of North Atlantic cultural achievement, and hegemony, today (notably: Christianity, a Graeco-Roman philosophical, political and legal heritage, science and technology) largely had their roots in Asia and Africa, in millennia before Europe rose to be a conspicuous cultural and political presence.

|

Descending from the Dean of Humanities' office to the packed room where the public defense of Mr Amougou's thesis is taking place |

|

The Dean of Humanities, University Yaounde-I, Professor Abwa, opens the public defense of Mr Amougou's thesis; from left to right: Professors Ondoua, former Minister of Labour, and supervisor of the thesis; Dinga, Dean of Philosophy, Catholic University of Central Africa (Yaounde); van Binsbergen (chair, and external examiner), Erasmus University Rotterdam and African Studies Centre, Leiden, the Netherlands; Dr Biya, Maitre de Conferences, Philosophy, Yaounde I. |

|

after the public defense: Professors Ondoa, Dinga and van Binsbergen with Dr Amougou and Mrs Amougou |

|

Surrounded by professors, septuaginarian Abbé Dr Hebga savours the honour done to him by Dr Amougou's thesis; the thesis even carries a personal dedication to him, which made one of the examiners wonder whether the candidate was aware of the potentially incestuous connotations of the project |

|

after the defense: Professors Godfrey Tangwa and Wim van Binsbergen, during the latter's seminar on 'Possibilities and impossibilities of African science' |

|

en route to the Grassfields, bridge over the Sanaga River; the PhD students are not yet exactly looking in the same direction |

|

computers bring the completion of the PhD thesis so much closer |

|

Inevitably, the foreign supervisor becomes part of the PhD student's family |

|

a major waterfall along the main road to Bafoussam: a locally recognised epiphany of the sacred |

|

Being presented with a notable's cane and ancient drinking horn, the twin's bag, the tree of peace (the green leavy contents of both baskets), a live chicken, and an assortment of loval vegetables and tuber crops, is to mark my most recent acquired identity: that of an adopted Bamileke prince. The tree of peace (fiekak, biagne) shown here looks like a variety of maize, which contrary to popular belief was present in West Africa prior to Columbus' initiation of European trans-Atlantic travels. It is supposed to have reached West Africa by westbound diffusion from the Indian Ocean, the Pacific, ultimately originating in the Americas |

|

the tree of peace (courtesy: |

|

in an aged Bamileke lady's traditional two-roomed house: an ancestral shrine consisting of a small number of stones on which ceramic imitations of human occiputs (skull tops); note the varied traces of recent offerings |

|

A SACRED-BUFFALO COMPLEX

WITH SUNDA REMINISCENCES? (A) the drinking horn referred to above; sign of a regional sacred-buffalo complex ultimately going back to Sunda migration from Indonesia in prehistory? |

|

(B1) side-stepping to the Kahare dynasty, western Central Zambia: unique in the region, the dynastic shrine is a buffalo skull raised on a debarked pole (van Binsbergen 1981). Although their area is infested with tsetse fly (possibly a relatively recent development since the late 19th century) Nkoya royals have cherished their cattle herds -- mainly derived from raids on their eastern neighbours, the Ila (with many Sunda traits of themselves). By the same token, at least one Grassfields royal (the Fon of Bum) has been known (Dick-Read 1964) to fondly cherish miniature cattle (Bos Brachyceros) as house pets. Needless to say that much of the Nkoya royal court culture, the royal orchestra etc. is strongly reminiscent of that of the Grassfields, although the latter is considerably grander |

|

(B2) King Mwenekahare Kabambi of the Nkoya people, Zambia (my adoptive father) performs at the last Kazanga annual festival before his death in 1993. He is clad in a leopard skin as royals' typical attire, and wears the royal headband with zimpande (Conus shell discs -- whose nearest provenance is the Indian Ocean). He is equipped with his ceremonial executioner's axe and with a basketry tray full of paper money (a trait with E Asian rather than African connotations!). The royal ancestral shrine (somewhat performatively raised in the festival grounds for the occasion) consists of a sacred shrub, at the foot of which a modern Chinese enamel bowl is dug in so that the rim is level with the soil. The king, who has just performed his royal dance, is shown in the act of kneeling at the shrine and drinking from the sacrificial beer that is in the bowl. The Kazanga festival is the revival, since the early 1980s, of a royal fertility festival that because of its violent nature and because of Lozi/Barotse overlordship, had been discontinued since the late 19th century. In royal circles the information circulates that the bowl was originally a human occiput, and the sacrificial fluid the blood of slaves who used to be sacrificed at Kazanga and at other royal occasions (intronisation, burial, initiation of a new royal fence, palace, and drum). These present-day spokesmen suppose that the occiput receiving the libation was also that of a slave, but by analogy with the Bamileke living tradition it makes much more sense to suppose that, originally, it was that of a royal ancestor. |

|

(C) A Bamileke buffalo mask |

|

(D) A buffalo sacrifice among the Toraja, Sulawesi, Indonesia (courtesy: http://www.trekearth.com/gallery/Asia/Indonesia/photo83692.htm ) |

|

the sanctuary of Fovu', a major epiphany of the sacred and source of initiatory legitimacy among the Baham (courtesy http://www.museumcam.org/baham/pays.php ) |

|

Bandjoun: royal establishment, still being reconstructed after the fire of a few years ago |

|

The palace of the Sultan of Bamum at Foumban. Note the skimpy equestrian statue in front. Among many other achievements, Bamum is famous for its alphabet, locally invented at the eve of colonial times; it is one of the few writing systems invented on African soil since the Ancient Egyptians and the Berbers, and a textbook example of 'stimulus invention' (Kroeber) |

|

the royal establishment of Baham: gaudily painted walls seclude the royal quarters |

|

opposite the above: the Royal Treasury / Museum of Baham |

|

Queens' quarters at Baham |

|

Bamileke High Plateau: the crater lake of Mbapit |

|

hiking towards the crater lake |

|

Wim van Binsbergen with Mr Nana, the skilful driver, during the hike |

|

Not exactly in the Western Grassfields, but near Buea, West Cameroon, a Roman coin from the time of Constantine the Great was found in the 1930s. To the left, a similar coin is shown (courtesy http://www.wildwinds.com/coins/ric/constantine/_alexandria_RIC_viii_032.1.jpg . Since there is no record of Roman Atlantic trade all the way to Mt Cameroon, specialists (Dick-Read 2005) surmise that this coin is one of the large number that at the time found their way to the Indian Ocean, where Roman trade was going through a revival under Constantine, and where Roman coins were much in demand (Bovill 1958). In that case the Buea coin, like cowries, Ifa geomantic divination and so many other items of culture, is likely to have found its way to West Africa via Madagascar and Southern Africa -- far away from the usual Arab trade routes connecting West Africa with West Asia and the Mediterranean |

|

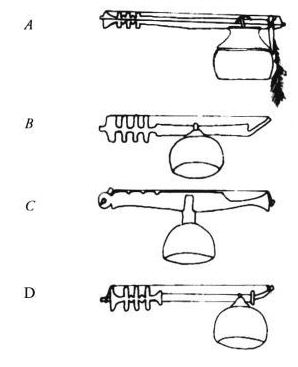

musical instruments form

another convincing indication of Sunda influence. Since

the work of A.M.Jones (e.g. 1972) xylophones are the

standard example. But the connection also applies to

otherinstruments, as these variants of bar-zithers

indicate (after Dick-Read 2005): A Olombo forest north bend of Congo river B Northern Mozambique (Makonde) C Sulawesi, Indonesia D Southwest Madagascar (Antaimore and Sakalava) Every visitor who comes to the Bamum royal museum is first exposed to a 10-minute sales talk in which local bar-zythers are demonstrated. Cameroon Grassfields bar-zithers oscillate between the above four types, coming closest to B and C |

|

Often it is tiny ornamental details, more than a general overall structure, that give the connection away. Compare these two snake-like terminal elements on slitdrums (after Dick-Read 2005), left from the Bamenda museum (for which Dick-Read did collecting c. 1960), right from Naga, Assam, NE India. Such decorative tell-tale details have also been cited to support the claim that major artistic archivements of the general Bight of Benin region (notably, the Benin bronzes) are considerably indebted to Buddhist/ Hinduist sculptural prototypes, e.g. from the Borobodur temple complex on Java. |

|

Ecstatic cults abound around the Bight of Benin including parts of Cameroon. Often the veneration of maritime elements is an important aspect of them. The images (courtesy Chesi 1980) show characteristic episodes of Vodun cults in Togo. They have also been a prominent expression in coastal East Africa and in SC Africa especially in recent centuries, where (at the eve of the penetration of Islam and Christianity) they have partly supplanted pre-existing local ancestral cults (van Binsbergen 1981). In the latter regions people often consider them spiritual winds that come from the east, on the wings of long-distance trade. Often appearing in conjunction with divination systems, there is much reason to see them as local applications of cultic systems of Madagascar, and ultimately of Sri Lanka and other Asian regions around the Indian Ocean, where ecstatic cults (often concentrating on healing and witchcraft) form an undercurrent of Buddhism and Hinduism. Note the transcontinental bricolage in the bottom picture, featuring among other items the Hindu deities Ganesha and Parvati, his mother. Specialists have for decades recognised the S Asian aspects of Vodun. |

|

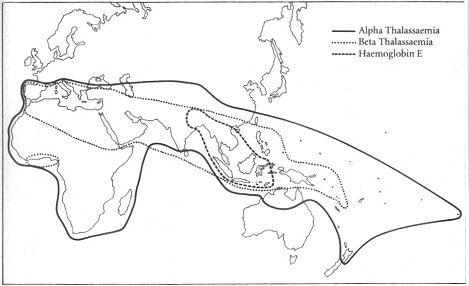

With the last few images, we are no longer reporting on a short trip to the Western Grassfields but have started to pursue the issue of Indonesian- Cameroonian continuities with material that could not possibly be collected in one short trip, and that was in fact collected and interpreted by others. To clinch the issue, let us consider the extensive genetic evidence. To the left I show (from Oppenheimer 1998/2001) the distribution areas of alpha and beta thallassaemia, heriditary forms of anaemia that render the individual less susceptible to malaria. There is a genetic argument indicating SE Asia as the place of origin of these mutations. Note that beta thallassaemia is mainly confined to a belt that extends N Spain to New Zealand, north of sub-Saharan Africa; but that it also occurs on the Bight of Benin -- although not in Madagascar, nor in Southern Africa. The latter threatens to make this finding less convincing as evidence of direct Sunda influence, but fortunately we have the far more detailed evidence from Cavalli-Sforza et al. 1994, showing similarly high readings for Madagascar and the East African coast -- fully in line with the Sunda hypothesis. |

|

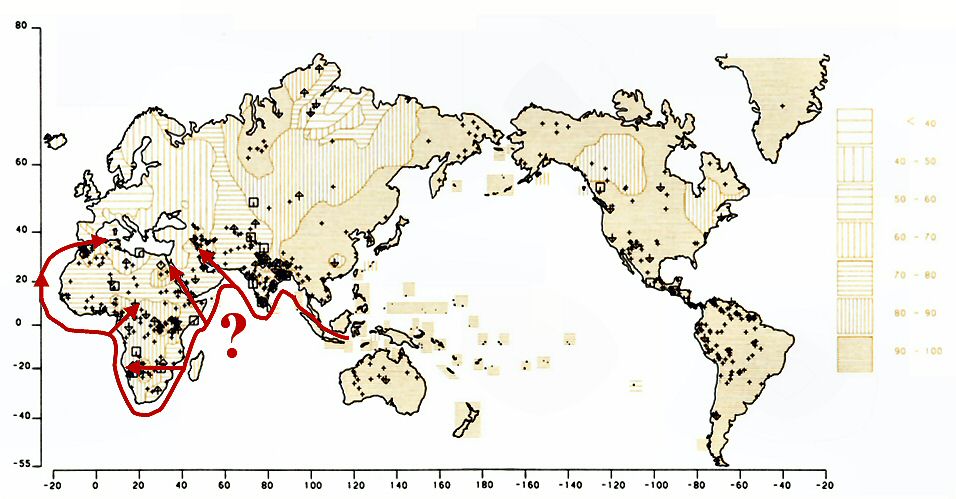

Cavalli-Sforza et al. 1994 also make abundantly clear that such Sunda effect on Africa can be attested in connection with a considerable number of classic genetic markers, especially the RH related ones. To the left is shown, for example, the particularly manifest Sunda effect on RH*D (Cavalli-Sforza et al. 1994, with my conjectural proposal for the path of the Sunda diffusion of that marker). |

| ADDITIONAL SPECIMENS OF GRASSFIELDS REPRESENTATIONAL ART | |

|

the Primal Mother nursing twins, seated on a stool with spider ornaments; Bamileke art* |

|

lost wax statuette: diviner with spider oracle and client* |

|

further Bamileke drinking horns, with spider (left) and leopard (right) ornaments* |

|

further Bamileke artefacts

featuring spider motifs: a pendant (left); a notable's

bed (right); and a lost-wax pipe*. As the detailed view (bottom) conveys very strongly, there are extensive technical and decorative details between the ajour-like 'hat' of the pipe and Indonesian copperwork, e.g. the Minangkabau flask shown next to the paper's detail (Galestin 1941) -- the parallels go much further than merely the use of spirals and double spirals, which of course has been an World ornamental art motif ever since the Upper Palaeolithic (Mal'ta near the Baikal Lake), and highly conspicuous in Bronze Age, Hellenic, Celtic and Gemanic/ Anglo-Saxon Ancient Europe |

|

further Bamileke artefacts featuring leopard depictions, the bottom one combined with spider motifs* |

|

The Grassfields (left) is one of the West African regions (cf. right, Ekoi, Nigeria) where the Janus motif is prominent -- another implied reference to a cosmogonic primal god of beginnings, which links sub-Saharan Africa to the Mediterranean (Roman Janus, Basque and Ligurian Basojaun), and South Asia (Ganesha) |

unless otherwise stated, photographs (c) 2006 Wim van Binsbergen; photographs marked * are (c) Klaus Paysan, courtesy Galerie Hermann, Berlin, Germany, see: http://galerie-herrmann.com/arts/art3/

return to Topicalities page | return to Shikanda portal

click

the image to return |

||||

|

|

|