The Manchester-related pictorial history of

social anthropology and of social research in Zambia is

surprisingly poorly covered at the Internet, which I why I took

the trouble to compose the present photographic essay. For

the reasons informing this particular selection of figures and

photographs, and background details, see my piece on the

Manchester School (still is Dutch, soon to be translated into

English). The illustrations below are largely available in

the public domain; they are cited for purposes of the circulation

of scholarly information, and with full references of original

provenance (clicking on a particular photograph will take you to

its original source; whether these websites are still accessible

is beyond my control). I acknowledge my indebtedness to original

copyright owners. Whenever the name of the photographer is known

to me, I have included it. This selection and captions © 2004

Wim van Binsbergen. Your comments, corrections and copyright

claims are most welcome via e-mail.

James G. Frazer, classicist and anthropologist

(1854–1941), pioneering theories of magic, of kinship,

and of sacred kingship; with his works, especially The

Golden Bough, he was the first (and only)

anthropologist to became a household word throughout the

English-speaking part of the world

|

Leo Frobenius, leading German Africanist (1873-1938),

indefatigable but contentious Africa traveller, great

collector of oral literature and local forms of art, and

founder of the diffusionist school of Kulturmorphologie

(Frankfurt)

|

Jane Harrison, highly original interpreter of Greek

ritual, influential classicist/anthropologist

(1850-1928), amongst her classicist colleagues; left to

right: H.F. Stewart, Gilbert Murray, Francis Cornford

|

Bronislaw Malinowski (1884-1942), born in Zakopane,

southern Poland, pioneer of anthropological fieldwork,

and for many the founder of British scientific

anthropology

|

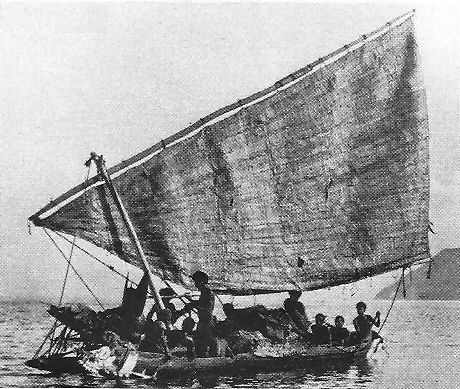

Trobriand Islanders on a sea voyage; it was during World

War I internment as a citizen of an enemy country that

Malinowski pioneered modern anthropological fieldwork

|

A.R. Radcliffe-Brown, leading theoretician of classic

British anthropology (1881 - 1955)

|

Grafton Elliot Smith (1871-1937), anatomist,

Egyptologist, and diffusionist anthropologist of the

early 20th century

|

E.E. Evans-Pritchard (1902 - 1973), embodiment of the

classic British anthropology from which Manchester formed

a radical departure

|

.

Cattle wealth among the Nuer today, southern Sudan; the

Nuer and Evans-Pritchard made each other famous

|

... ...

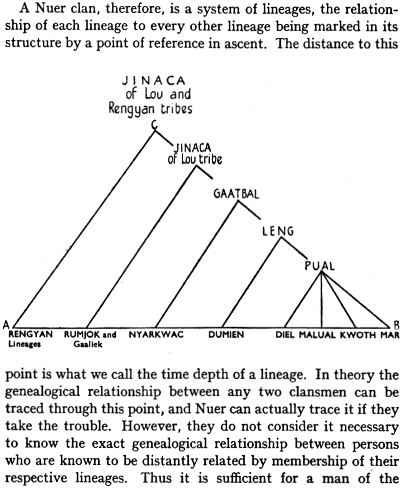

Evans-Pritchard, The Nuer,

page 201: The Nuer was a particularly effective and

influential description, in terms of interlocking systems

of segmentation at the family, and clan level, of the

social organisation of a (before colonial conquest)

stateless society. The elegance, simplicity and

transparence of the book's modelling, enhanced by

Evans-Pritchard splendid prose style, were irresistible

but (or so the Manchester School thought) too consistent

to be true

|

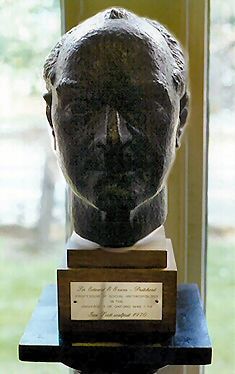

E.E. Evans-Pritchard’s bust in the Tylor Library,

Oxford, United Kingdom

|

A scale model of a Tallensi homestead,

northern Ghana, where Meyer Fortes (1906-1983) conducted

fundamental fieldwork on social organisation and religion

|

Audrey Richards (1899-1984), a student of Malinowski’s,

and the first to write a fully modern ethnography of a

community in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia): Land,

labour and diet in Northern Rhodesia (1939). |

.

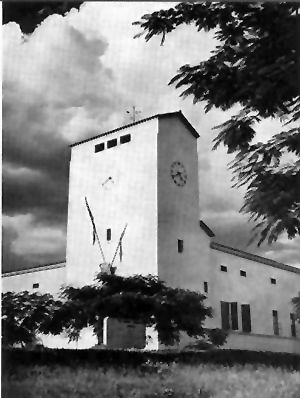

The Rhodes-Livingstone Institute was initially located in

the town of Livingstone in the far south of Northern

Rhodesia. Livingstone was the colony’s capital until

the mid-1930s, after which the seat of government was

shifted to the more centrally located Lusaka, until then

a minor railway siding. The Rhodes-Livingstone buildings

at Livingstone were to house the Rhodes-Livingstone

Museum, which today is struglling on under ever

increasing hardship

|

Monica Hunter did research among the

Pondo of South Africa, and with her husband Godfrey

Wilson she studied the Nyakyusa of southwestern

Tanganyika (now Tanzania), before the couple embarked on

a pioneering study of social relations among the urban

migrants in the central Northern Rhodesian town of Broken

Hill (now Kabwe), created immediately after the colonial

conquest (c. 1899) because of its rich resources in lead

and zinc, long before the much more rewarding copper

reserves were discovered further up north, in what was to

be the Copperbelt. The Wilson's Kabwe research resulted

in The Economics of Detribalization in Northern

Rhodesia, 2 vols (1942, so published after Godfrey

Wilson's death). Apart from Ellen Hellmann's study of the

'native slum' Rooiyard in South Africa

(subsequently to be republished as a Rhodes-Livingstone

Paper in 1948), no such study had yet been undertaken in

South Central and Southern Africa. Godfrey Wilson was

founder-director of the Rhodes-Livingstone Institute, but

soon after the outbreak of World War II he committed

suicide, allegedly because of his pacifist convictions.

This changed the course of Gluckman's life and of the

history of anthropology: Gluckman, until then a young

Ph.D. exploring Barotseland and relishing the princely

status that was accorded him there, became director of

the Rhodes-Livingstone Institute.

|

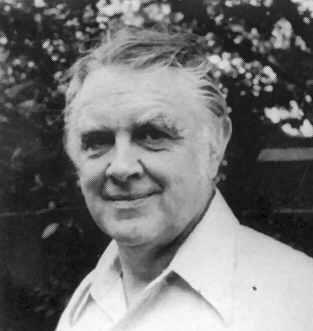

Max Gluckman (1911-1975), ca. 1970; note the signature

bottom right, sign of celebrity aspirations. On the other

hand, he appeared to be relatively modest concerning the

paradigmatic shift that the Manchester School

represented, and admitted: "A science is any

discipline in which the fool of this generation can go

beyond the point reached by the genius of the last

generation." (But, in a dialectical way rather

typical of Gluckman's thinking, this expression takes on

a totally different quality when considered from the

perspective of the generation that came after Gluckman,

and then would claim not stupidity but genius for him).

|

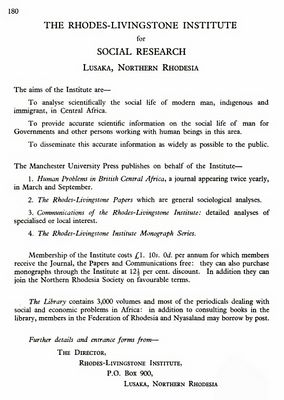

Publicity

for the Rhodes-Livingstone institute, late 1950s (click

on thumbnail to enlarge)

|

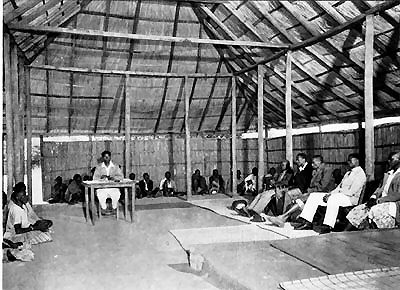

The Barotse king’s hall, Barotseland, 1940s, where Max

Gluckman did much of his Barotse fieldwork

|

Paramount Chief Sir Mwanawina III KBE (Knight of the

British Empire) (1888- 1968) of the Barotse, dressed in

state in the admiral’s uniform which the British crown

had donated to his most famous predecessor, Lubosi

Lewanika. Mwanawina’s successor was Mwendaweli, who had

earlier served as Max Gluckman’s research assisant in

the 1940s

|

Barotse kuta (royal court) in progress, probably in the

1950s

|

Labourers from the Rand Gold Mines returning home up the

Zambezi in the 1950s. From the late 19th century onward,

temporary labour migration to the mines and commercial

farms of South Africa and Southern Rhodesia was a major

source of cash for the rural population, only partly

diverted by the emergence of mining towns on the

Copperbelt in the late 1920s. Migration, especially

circulatory labour migration, was the backbone of the

economies of South Central and Southern Africa, but no

adequate scientific approach to this phenomenon was yet

available, and Manchester School researchers (especially

Mitchell and Epstein) devoted much of their time and

energy to fill this gap, both descriptively and

theoretically.

|

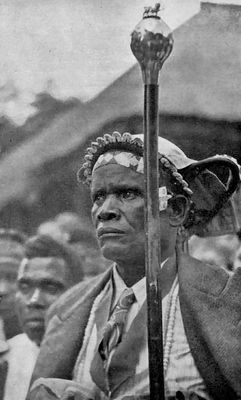

Paramount Chief Kazembe XV at Luapula, focus of Ian

Cunnison’s research around 1950; photo T. Gorecki

(unfortunately I have no details concerning this king's

dates of birth and death)

|

Much of the strength of the

Rhodes-Livingstone Institute derived from its excellent

and diversified publication strategy, comprising four

different series (1. cyclostyled Communications; 2.

printed Papers; 3. printed books; 4. the journal Human

Problems in British Central Africa / Rhodes- Livingstone

Journal); most of these were eventually accommodated

with Manchester University Press, the Manchester School's

house publisher

|

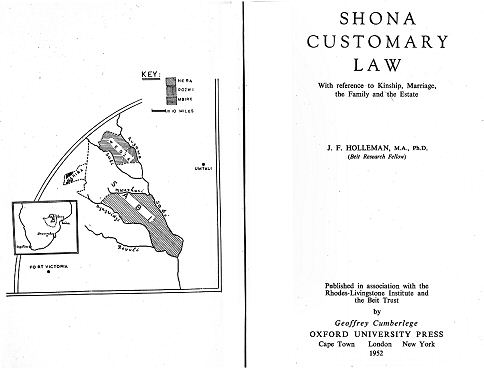

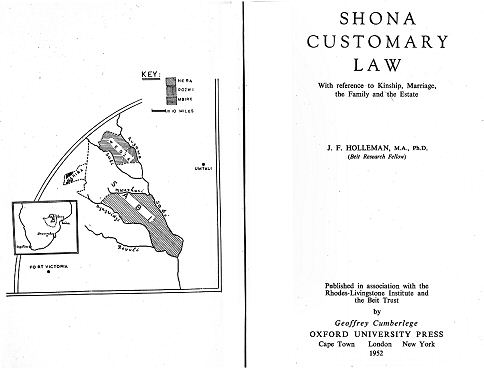

The

whole of British South Central Africa (present-day

Zambia, Zimbabwe and Malawi) was the work space of the

Rhodes-Livingstone Institute, but given Max Gluckman

junior status when he became director in the early 1940s,

the earlier anthropological research in this vast

territory was by no means controlled by Gluckman and

lacked the Manchester School touch. In Southern Rhodesia

in the 1940s, Hans Holleman, son of a Leiden professor of

Indonesian adat law, developed into one of the

most prominent students of African law with, as he

declared to me in the late 1970s, only a minimum amount

of 'rubbing shoulders with the Manchester crowd'.

|

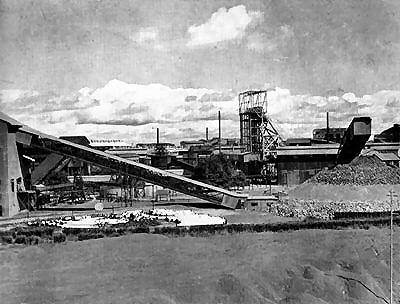

Luanshya, the most typical of the Copperbelt mining towns

which emerged in Northern Rhodesia from the late 1920s

onward

|

a map

of late colonial Northern Rhodesia from the settlers'

point of view: only places with a substantial white

population are marked, and hotels and rest camps are

specifically indicated (click on thumbnail to enlarge)

|

(click

to enlarge) (click

to enlarge)

For the African inhabitants of Northern

Rhodesia, a rather different map was drawn up, clearly

demarcating, and distinguishing by contrasting colours,

the various 'tribal' areas into which the territory was

administratively divided; the assumption was that these

divisions coincided with linguistic and cultural

distinctions, thus reifying (through the cbinary

opposition of ethnic names) cultural gradients that were

in fact much more continuous, in most cases.

Anthropologists used this map with the same enthusiasm as

administrators. A copy of it graced Brelsford's Tribes

of Zambia (1956, repr 1965) -- written by a colonial

administrator dabbling in ethnography (like so many of

his colleagues), but also Audrey Richard's splendid, and

deservedly classic, ethnography Land, labour, and

diet in Northern Rhodesia (1938). As the Kwacha

price tag, bottom right, indicates, the map was

uncritically reprinted in post-colonial times by the

Zambian Survey Department, the country's official

producer of maps. It formed the basis of Kashoki's map of

Zambian languages in the late 1970s. The fantasms of

colonial ethnography and administration have thus

continued to be seeded back into postcolonial popular

appropriations.

|

Kitwe, to develop into the main town of the Northern

Rhodesian Copperbelt, ca. 1955

|

Copperbelt dancers, 1950s. During weekends, African

miners on the Copperbelt, dressed in their Sunday best,

would perform dances reminiscent of their home areas. In

this way they articulated aspects of ethnicity and of

urban-rural relations which were to become the topic of

Clyde Mitchell’s famous essay The Kalela Dance

(1955).

|

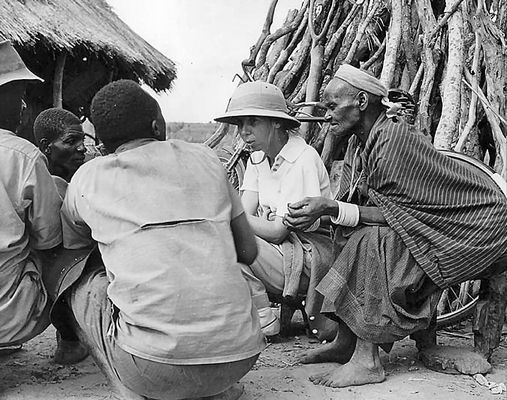

Elizabeth Colson (centre) (1917- ), probably early 1950s,

during fieldwork among the Tonga; note the helmet

|

Victoria University, Manchester, where Max Gluckman was a

Professor of Anthropology from 1949 onwards; © 2000-2004

Dr. Falco Pfalzgraf

|

.

By all accounts, Max Gluckman exercised a strong hold

over his students, disciples and junior members of staff.

Manchester School identity means that one shares in a

vast repertoire of rumours and anecdotes associated with

Gluckman's autocratic but benign leadership in the

1940s-60s. One persistent rumour is that he forced

everyone to support Manchester United, the major local

soccer club. Watching their life performances in the

stadium, or failing which, their appearances on

television, is alleged to have been compulsory for

Manchester School members when ‘home’; ©

www.webaviation

|

(click for enlargement) (click for enlargement)

Another persistent rumour is that Max

Gluckman persuaded his followers to be card-carrying

members of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

Considering the (from our present point of view) almost

inconceivably exploitative and racialist labour

conditions to which African workers were subjected in

Northern Rhodesia and throughout the Federation of

Rhodesia and Nyasaland, and also considering the

courageous solidary stance which most Manchester School

members adopted vis-a-vis their African hosts, friends

and junior colleagues in research, communism may well

have been the only option of integrity available. At the

same time Europe was in the throes of Cold War demagogy,

so this option was not chosen lightly, as several

Manchester School researchers were to experience in their

personal and political careers.

|

Lord Simon of Wythenshawe, Sir Ernest Emil

Darwin Simon, 1879-1960. After working in the family

engineering business Ernest Simon became a Liberal MP in

1923. He joined the Labour Party in 1946 and was a

founder of New Statesman magazine. In 1947, the

Labour Government gave him a peerage and appointed him

BBC Chairman. A respected authority on post-war

Britain’s rebuilding, he always kept close connections

with Manchester and his family business. He chaired

Manchester City Council until 1957. At the University of

Manchester, visiting fellowships and a professorship were

endowed in his name; the incumbents were housed in the

Simon residence near Victoria University, Manchester, and

attended on by what remained of Lord Simon's former

domestic staff. In the heyday of the Manchester School,

several of its members were incumbents of the Simon

Professorship, includingVictor Turner and Jack Simons

(the South African legal sociologist and freedom

fighter). In 1979-1980 I also had that honour.

|

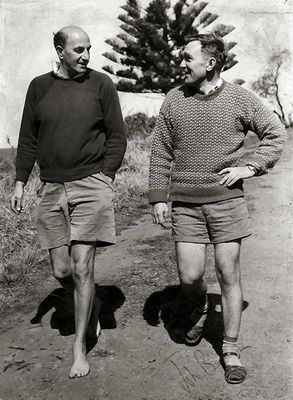

Max Gluckman and John Barnes (1918 - ) at Canberra

University, Australia, 1960; note the signature bottom

right – again, these were scholars consciously aspiring

to celebrity status; but also note Gluckman's bare feet.

Initially investigating the political organisation of the

Ngoni (a Nguni offshoot which the mfecane

upheaval in early 19th c. CE Southern Africa propelled

far up north), Barnes was later to pioneer network

analysis. Remarkable is his piece 'African models in the

New Guinea highlands' (Man 1962), which explores

the applicability of Africa-based segmentary model of

social organisation to Oceania.

|

Max Gluckman (left) at a party at home, 1959. To the

right is Richard Werbner, then a most promising student

aged c. 22; later he was to marry Gluckman’s

brother’s daughter Pnina Gilon, born and bred in Israel

since that is where her father settled from South Africa.

This marriage reinforced Werbner’s role as keeper of

the Manchester School inheritance after Gluckman's demise

in 1975. The person in the middle is Maurice Ginsburg,

without obvious connection with the Manchester School.

|

Sigmund Freud (1856 - 1939), founder of

psychoanalysis, in his Vienna study. Concentrating on the

small-scale social process at the level of the village

and the urban ward, mainly in Africa, the Manchester

School never had much of a discourse on the hidden,

subconscious drives in human behaviour. Instead it

emphasised the explanatory value of agency: the

individual actor's conscious strategies of manipulating

social norms and inchoate structures on the basis of the

preceding historicity (the unique and unpredictable,

accumulative unfolding) of the social process. However,

psychoanalysis (albeit not by Freud of course, who had

died in London before Gluckman ever set foot in

Barotseland) was alleged yet to play a role at Manchester

as an uninvited guest: as the intended remedy for

Gluckman's profound midlife and leadership crises. Rumour

(that is, my interview with Jaap van Velsen, Manchester,

April 1976) has it that Gluckman's remarkable book

production in the late 1950-mid 1960s had much to do with

the need to pay his therapist's bills; not unlike the isanusi

or isangoma diviners at a Zulu king's court (the

setting of Gluckman's Ph.D. research), those involved

attributed to this therapist disproportionate influence

over the affairs of the anthropology department.

|

Victor Turner (1920-1983), the one Manchester figure who

strayed furthest from the Manchester path, and in the

process gained world fame with his lasting contributions

to religious studies. A persistent Manchester rumour

interprets Turner's first major book, Schism and

continuity in an African society (1957), as a key

novel echoeing the struggles for leadership and

recognition, 'order and rebellion' (the title of one of

Gluckman's books), that constituted the Manchester

School.

|

|

|

(click

on thumbnails to enlarge)

The most detailed and

convincing example of the Manchester School

approach to rural communities in South Central

Africa was Jaap van Velsen's The politics of

kinship (1964, based on his 1957 Ph.D.),

dealing with Tonga villages in Nyasaland (now

Malawi). The book is classic ethnography in its

methodology of taking the combination of a

village map and a genealogy (as shown here) as

essential point of departure for social analysis.

However, the book demonstrates that it is not

corporate group interests and fixed norms, but

momentary concerns and strategies in an ongoing

social process, which determine the shape and

outcome of conflicts; what makes Central African

villages tick, is not a kinship-centred culture

('custom'), but local-level politics

within the kinship realm. The preface of the book

was written not by Gluckman but by Clyde

Mitchell, not only as the Malawi specialist, but

also as someone who probably contributed as much

to the success of Manchester as Gluckman did

himself. Mitchell was the intelligent, modest,

socially skilful, patient lieutenant who could

negotiate, much better than Gluckman himself,

between local ethnographic facts, complex and

diverse methodological requirements (including

numerical ones), and conflictive and exuberant

researcher personalities, like Jaap van Velsen's.

The latter was a Dutchman with an Indonesian

background, whose justified disgust with Dutch

colonial politics (especially the violent

'Politional Actions', after WW II) had made him

turn to Great Britain. The politics of

kinship was his first and last book, and its

writing was agony; not only because of oppressive

power relations and bizarre personality clashes,

but also because the book was at the same

time the culmination and the swan's song of

Manchester rural ethnography -- bringing out

beyond repair the limitations of its paradigm, especially

its extreme conception of the social process as a

drama confined to a strictly local theatre.

Characteristic of this agony was that van Velsen

felt compelled to excise, from the book's very

galley proofs, an entire chapter on labour

migration, which (with that amount of empirical

detail, and in the organic context of the overall

ethnographic argument on Tonga society) was never

to appear in print elsewhere. Yet it was a unique

opportunity to show how the social drama in the

Tonga villages reflected much wider structural

arrangements in the political economy of South

Central Africa, and of the world at large,

regardless of whether the villagers were

conscious of such arrangements, and made them

part of their conscious maximalisation

strategies.

|

|

While

for the analysis of rural settings in South Central

Africa the Manchester School relied on the notion of an

inchoate social structure full of contradictions and

options, gradually emerging in the social process and

best visible in conflict situations, for urban settings

the pioneering Copperbelt studies of Epstein and Mitchell

began to stress the model of the social network between

individuals. Here we see Bruce Kapferer's inticate model

of the network informing an workshop conflict in Zambia,

described in Mitchell's seminal collection on urban

networks (1969)

|

Andre Kobben (1925- ), focal point of classic cultural

anthropology in the Netherlands in the 1950s to early

1970s, here depicted in 2004, at the age of 79, still

going strong. Although his own fieldwork (Ivory Coast,

Surinam), his theoretical passions (cross-cultural

comparison) and his international network in the North

Atlantic (mainly USA and Oxford) put him at considerable

distance from Manchester in his own work, he successfully

mediated the Manchester School influence to his main

students. From the mid-1970s onwards, he has concentrated

on North Atlantic sociology, methodology and the

philosophy of the social sciences, and has been less of a

leading force in Dutch anthropology

|