THE LAND AS BODY

Marxist or symbolist approaches to the medical domain among the Manjaks of Guinea-Bissau

Wim van Binsbergen

|

THE LAND AS BODY Marxist or symbolist approaches to the medical domain among the Manjaks of Guinea-Bissau Wim van Binsbergen |

|

Abstract[i]

Although

neo-Marxism informed the author’s field-work on the

therapeutic effectiveness of rituals among the Manjaks in

northwestern Guinea-Bissau, the explanatory value of materialist

models turned out to be limited. Far from collapsing under the

impact of capitalism (through migrant labour in Senegal and

France), Manjak society keeps up an intact symbolic order.

Migrants continue to interpret their physical and mental

disorders in local terms and to participate in expensive rituals

which absorb their capitalist earnings. Thus they submit to the

gerontocratic order, restoring their roots in a cosmology in

which the (orifice-less) Perfect Body ultimately consists of the

ancestral Land itself. Spatio-temporal belonging, filiation,

domestic kinship power and bodily functions thus merge,

illuminating many aspects of illness behaviour and its

expressions in ritual and everyday life. Neo-Marxism,

epistemologically linked to societies under capitalism, scarcely

explains this repertoire of symbols — yet helps us to

pinpoint its unexpected vitality.

The relations between the symbolic order and the political economy of any social formation are unmistakable and often throw an interesting light upon the specific structure and dynamics of the symbolic order. But the potential of such analysis gets spent, and after initial illumination it soon turns out that some of our fundamental research questions tend to become remain unanswered (if they do not become obscured and misdirected) under a materialist approach. The reasons that made some of us adopt that approach in the first place remain valid (cf. van Binsbergen 1984a). These reasons do not primarily lie (contrary to Droogers 1985) in the academic market incentives at fashionable theoretical innovation, but in the following considerations which together somehow sum up the current neo-Marxist inspiration:

(a) A rejection of the

philosophical idealism which for almost a century (under the

impact of Durkheim and his philosophical forbears) has dominated

social anthropology in general and especially religious

anthropology, and which has claimed an independent dynamics sui

generis for cultural and symbolic phenomena.

(b) The attempt to share, albeit it

only in the vicarious form of scholarship, in significant forms

of protest and struggle (between classes, ethnic groups,

generations, sexes; against statal, colonial and/or racial

oppression) in the present or the past, and adopting there the

cause of the underlying groups. Once we have understood that

oppression always has roots in the political economy, our good

intentions might easily lead us to concentrate on such roots

alone, projecting a political economy of exploitation and

oppression onto any situation involving any of the social groups

listed here, and materialistically assuming the primacy of that

political economy over whatever symbolic or ideological

expressions that group interaction might take. Ultimately the

relative powerlessness of our own social-scientific academic

production in North Atlantic society may be a principal factor in

our desire to vicariously liberate socially and distant other

people — if only on paper.

(c) Neo-Marxism has proposed new

answers in the prolonged struggle between, on the one hand,

cultural imperialism as propounded by North Atlantic society in

general as from the nineteenth century, and, on the other, the

extreme, kaleidoscopic fragmentation which cultural relativism

has propounded, as the main stock-in-trade of classical

anthropology. Neo-Marxism has helped us to understand how the

logic of capitalism (as mediated through bureaucratic formal

organizations) is one of the major structural implications, and

conditions, of such cultural imperialism — albeit that we do

not yet fully understand the place of anthropological

intellectual production in this set-up.[ii]

More

importantly, the paradigm of the articulation of modes of

production — one of the major contributions of neo-Marxism

— has allowed us to see a limited number of broad patterns

of fundamental structural correspondences cutting across the

dazzling multiplicity of cultures, and to anchor these patterns

in a few simple basic forms of exploitative relations of

production such as have repeated themselves in time and space:

exploitation of women by men; of youth by elders; of villages by

unproductive aristocratic or royal courts; of labour by capital.

The assumption that each of these basic forms of exploitative

relationship (each of these modes of production)

represents a unique logic of its own, expressed in recognizable

and repetitive (however superficially different) economic,

social, political and ideological forms, has begun to enable us

to view the manifold contradictions such as characterize all

social formations, and particularly those of the modern world, as

the dynamic interplay between modes of production seeking to

impose their hegemony over others in the same social formation.

Here the

problem is that our understanding of the capitalist mode of

production, its logic of commoditification, and the

contradictions it generates in contact with other modes, has

reached considerable maturity (after all it is the mode of

production which has produced — albeit somewhat

antithetically — our own discipline, and which has largely

dictated the patterns of our personal lives inside and outside

the lecture-room and the study), whereas our appreciation of

other modes of production and their logics, as conceived in the

same materialist framework, is still very tentative, exploratory

and intuitive. What immense stores of knowledge anthropology has

built up about other modes of production is largely cast in a

non-Marxist, idealist idiom; but (despite individual attempts) we

have not yet set out to systematically decode this body of

information in neo-Marxist terms, and perhaps may never succeed

in doing so entirely because of the material and ideological

constraints to which our own production of academic knowledge is

subjected in the context of our capitalist society. As a result,

classical and neo-Marxist anthropology continue to constitute

largely separate realms of meaning and explanation, sometimes at

daggers drawn, often simply incapable of relating to each other

and of illuminating each other’s analyses. The awareness of

a vast, occasionally rich, profound and beautiful edifice of

classical description, analysis and theory leaves the more

sensitive neo-Marxist anthropologist uneasy about the

abstraction, generality and superficiality of his or her own

tentative materialist approach. Yet one hesitates to trade the bad

conscience this generates, for the false

consciousness an idealist classical approach would constitute.[iii]

The

heuristic potential and illuminating power of the neo-Marxist

position has been brought out time and again with regard

particularly to the analysis of such innumerable social

situations in the contemporary Third World as are characterized

by peripheral capitalism. In the specific

field of medical anthropology, the ubiquitous commoditification

of health care, along with the general commoditification of the

productive and consumptive experience of its Third World users in

social formation increasingly dominated by peripheral capitalism

(proletarianization: dependence on wage labour and on monetarized

markets for food, housing, labour, entertainment etc.); the

increasing dominance of formal bureaucratic organizations in the

medical domain — partly through the impact of the colonial

and post-colonial state whose logic owes much to capitalism, and

partly because this is the organizational form in which (First

World, pharmacological) capital seeks to structure the production

and marketing of health commodities; the very emergence of the

medical domain as a separate identifiable sector in

peripherally-capitalist Third World societies; the spin-off of

these processes in the way of indigenous healers exchanging the

time-honoured local forms of their trade, for innovations

mimicking the cosmopolitan doctor’s office, bedside manner,

techniques, remuneration and professionalization — all these

highly familiar topics in medical anthropology today bear witness

to the relevance of a neo-Marxist perspective.

Yet this

needs scarcely surprise us: of course an approach that started

out as an analysis of capitalism in the first place, should be

capable of gauging rather adequately the impact of peripheral

capitalism in selected social domains such as the medical one.

Our

analytical problems, as medical anthropologists seeking to apply

a neo-Marxist paradigm, really begin when we turn to historical

societies which pre-dated capitalism, or to contemporary

societies where, for one reason or another, the inroads of the

capitalist mode of production have been slight, ineffective,

blocked. Is a neo-Marxist approach capable of

analyzing societies without capitalism? Or is

neo-Marxism only an epistemological echo of the capitalist

ideological make-up of North Atlantic society, capable only of

discerning whatever is fundamentally, ontologically kindred to

it? Having explored elsewhere (van Binsbergen 1984 and

in press) the amazing impenetrability of Manjak society in

northwestern Guinea-Bissau for capitalist encroachment , the

Manjak case as discussed in the present paper represents a far

from promising test case for this question.

Neo-Marxist materialism came as an

afterthought to my main Zambian field-work in the 1970s, and

while it has proved incapable of catching up with my data on

Tunisian popular Islam as collected in 1968 and 1970,[iv] it formed the context of my research

in progress in Guinea-Bissau. Moreover, that country’s

liberation struggle has had great symbolic and emotional value

for radical North Atlantic academics ever since Basil Davidson

(1969, 1981) adopted it; for better or worse, it still stands as

a creation of one of Africa’s main radical theoreticians,

Amilcar Cabral. When the Bissau Ministry of Health needed

anthropological information on the psychiatric therapeutic

potential of local, non-cosmopolitan healers, the request

appealed to me not only because it offered the opportunity of an

inside view and a personal intellectual contribution to that

country, but also because it would force me to confront my

theoretical views with new field-work in which symbolic phenomena

and their practical effects on people’s lives would be so

central that I could not easily take refuge in some superficial

political economy generalizations, but would be forced to look

for neo-Marxist interpretations as rich and as profound as the

best classical anthropology would be capable of.

Manjak rituals[v]

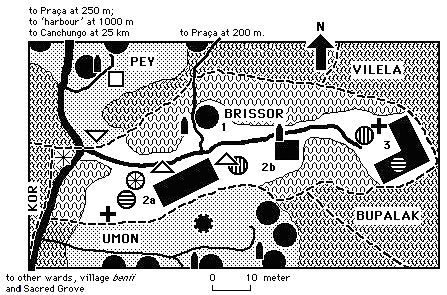

The research was situated in the Manjak area in the northwestern part of the country: a region where autochthonous cults, foremost the cult of the Land (Mbos), are still immensely powerful and where the world religions (Christianity and Islam) have little penetrated. In some respects this was the most intensive and ‘direct’ field-work in my career: for the first time I did not have my own household but stayed with a local family, whose head was a senior Land priest to boot, and I worked without an interpreter during most of the research. However, with all this rapport the free flow of information remained checked by the extreme secretiveness of Manjak culture: within the villages and their various constituent wards I could readily participate in the ongoing social process and in collective ancestral and other rituals as directed at the multitude of local shrines (cf. figure 1), but the Sacred Grove just outside the village (centre of the Land cult and of adult male ritual and social life in general) remained closed to me, and only sporadically could I accompany individuals when their frequent personal quests for healing and good fortune led them to the napene priests — the incumbents of a cultic complex (only loosely associated with the Land cult) whose many oracular shrines (puból) were also found all over the villages. It was mainly as a client or patient myself that I managed to gain frequent access to the rituals of the pubols and of the region’s most important regional cult (that of Mama Jombo in Coboiana, at a distance of c. 50 km) — and in doing so I merely followed in the footsteps of the many Portuguese and Senegalese strangers these shrines have accommodated over the years.

| village path | compound path | ward boundary | |||

| other wards | trees | ruin | |||

| well | kitchen hut | cattle pen | |||

| bathroom hut | name of ward | open toilet place | |||

| dwellings (rectangular: modern, iron-roofed; round: traditional, thatched) | deity's shrine | ||||

| distinct compounds (compound 2 consists of the larger men's house and the smaller women's house | benii (assembly place) belonging to the Pey ward (with shrine and cemetery | ||||

| a collection of ancestral shrines | oracle hut | ||||

Figure 1. A typical Manjak ward.

The

Manjak situation was my first personal experience not only with

an African society where the flow of information was so utterly

restricted and privacy so highly valued (one can imagine both the

advantages and the disadvantages of this state of affairs from a

field-worker’s point of view), but also with a still viable

gerontocracy that had successfully withstood the eroding effects

of capitalism and the modern state. The latter aspect I found

difficult to appreciate. In day-to-day interaction it was brought

home to me that I did not qualify as an elder (in a society where

age, and age differences, formed a constant obsession for the

participants, and even men in their sixties still recognized

their junior status vis-à-vis the ‘real’ elders, their

seniors); similarly I was constantly reminded of the fact that,

as a non-initiate, my status was much lower even than that of my

local age-mates. And beyond this personal level (which was not

untinged by personal projections referring to my own social

position as a son, a father, and a senior academician, in Dutch

society) there was the neo-Marxist paradigm,[vi] which had taught me to consider the

relation between elders and junior members of their society

(women, and young men) as essentially exploitative: was not such

exploitation the pivot on which the ‘domestic’ mode of

production hinged? Instead of the post-revolutionary

society I had been prepared for and with which I might easily

have identified — one where young people had come to

formulate a new and inspiring social order —, I found myself

in an unexpectedly archaic social order fully dominated by

elders. The proceeds of the region’s massive and

prolonged labour migration to Senegal and France mainly seemed to

be controlled and appropriated by the elders, not so much (as

commonly elsewhere in Africa) in the form of bride-wealth or

other local capital investments, but certainly in the form of

relatively very expensive ritual offerings (of rum and animal

sacrifices) imposed by cults whose leaders were elders, and

(after the Land had had its libatory share) largely consumed by

these elders. Migrants to other parts of Guinea-Bissau and to

Senegal would usually return at least once a year, with money

mainly spent on ritual offerings, and while those in France of

necessity observed longer intervals, much of their distant

experience was articulated in terms of relations with the Land

and local shrines, money for sacrifices would be transferred, and

they would make a point of attending at least the local

initiation festival that, once every twenty years, forms the

culmination of the cult of the Land. Contrary to current

insights, the migrants’ participation in the capitalist mode

of production did not seem to serve the reproduction of that

mode, but of the local modes of production under gerontocratic

control (van Binsbergen 1984b). Political economy yet again.

Not without ethnocentric projection,

from this tentative analysis I tried to proceed — conform my

research plan — to pronouncements as to the therapeutic

effectiveness of the various cults in which Manjak participants,

including migrants, were involved.

One of

the striking features of Manjak rituals (which are invariably

prompted by illness) is the lack of dramaturgic and symbolic

elaboration. The rituals have a low degree of formality. They are

poor in symbolism and expression, little elaborate, and lack a

dramaturgy of tension and relief. They are usually limited to a

few minutes of pouring, drinking, killing, a short

mumbled prayer, more drinking, after which follows a hasty

retreat to productive activities in the paddy-fields or cashew

and palm groves. This applies to most ancestral and Land ritual.

Only the principal ancestral ritual (the erection of a shrine for

a deceased kinsman, for reasons of human demography a relatively

extremely infrequent occurrence), may be more elaborate in that

it may involve the monotonous drumming of praises on talking

drums, and a collective meal or drink in which also members of

neighbouring wards and villages, and particularly age-mates, take

part along with members of the deceased’s ward. Commensality

is also an aspect of the occasional rituals staged by priestly

and other occupational guilds. Despite the very considerable

alcohol consumption, local ritual is invariably very sober,

simple, matter-of-fact, direct. Ritual concern and tension turned

out to entirely concentrate on the material requirements that had

to be met even before a ritual could be staged: people, and

especially returning migrants, rush up and down the all-weather

road to the market town of Canchungo (formerly Teixeira de Pinto)

for ever more rum and animals in order to discharge constantly

ramifying and increasing ritual obligations imposed by divining

and officiating elders against whom they have no appeal. Those

involved spend a fortune on this, yet do not seem to enjoy it in

the least, nor derive any catharsis from it, at least not such as

could transpire in my day-to-day contact with them. On the

contrary, what did come across was their mounting state of

stress, when confronted with their powerlessness in the face of

the officiants’ demands, with their own dwindling resources

in terms of time of money, and with the fact that the

post-revolutionary Guinea-Bissau economy often made it impossible

to find a taxi or buy sacrificial items even if the money was

available.

In this

set-up, I tended to interpret these rituals as primarily the

financial and symbolic submission, on the part of women and young

men, to their elders: both directly (as officiants), and

indirectly (the supernatural agents venerated in the cults were

thought of as being just as demanding and forbidding as the human

models, the elders, after whom they would appear to be shaped). How

could such submission ever be wholesome? I was

prepared to accept that when elders were both officiants and

clients/sponsors in these rituals, the result might benefit them

emotionally and spiritually — reinforcing the gerontocratic

dominance they were enjoying also outside the ritual sphere. But

I tended to deny all therapeutic effect when women and young men,

at the hands of elders that already dominated their non-ritual

life, saw this domination again reinforced in a cultic setting.

The cost of ritual participation, and the clients’ lack of enthusiasm

in the original, religious sense of the word (i.e.

‘divine rapture’), all seemed to corroborate such a

conclusion.

I was

however prepared to make an exception for the napenes’

cultic complex. Its loose association with the Land

cult was clear, even though no ritual activity could take place

at the pubols that was not immediately

complemented by a similar offering at the Sacred Grove. The pubols

(thick-walled, dark, secluded, with one or more

typically two conspicuous libation basins, and crammed with

paraphernalia: shells, horns, animal skulls, etc.) were of a very

different construction from the Land shrines outside and inside

the Sacred Grove: the latter were mere miniature thatched huts

without walls and virtually lacking further specific features or

paraphernalia. The pubol officiants were

specialist ritual entrepreneurs who did not have any ex

officio social or political status in their wards of

residence nor in the Land cult. And the pubol rituals

of divination and healing were intimate, full of subtle

dramaturgic and symbolic effects, and unmistakably cathartic.

Having repeatedly experienced, as a client, the liberating forces

of the napenes’ cultic idiom even

across cultural and linguistic boundaries, this was a conclusion

I could not very well escape. But again, the napenes

did not necessarily occupy key positions in the gerontocratic

structure of this society — while the officiants of the Land

cult did.

Obviously,

however, neither a field-worker’s aesthetic appreciation,

nor his projection of personal or theoretical views as to what

constitutes a pleasant sort of society, nor even his personal

existential experiences with divination and healing, provide

sufficient clues to approach that crucial but ill-studied aspect

of African religion: therapeutic effectiveness. What

was needed was an assessment of occurrences of physical and

spiritual disorder, in an attempt to trace the structural

conditions under which people had fallen ill, the various local

and cosmopolitan therapies they had pursued, and their outcome in

the short and the long term. This involved a study (mainly

through general observation and participation in the host family,

in the village and at the local dispensary of cosmopolitan

medicine), of symbolism and practices towards the body, illness

and healing; and the sort of diagnostic in-depth interviews and

observations my psychiatric colleague in this project (a

Western-trained psychiatrist with several years of practical

experience in Guinea-Bissau) enabled us to conduct.

Not

surprisingly, in the West African context, the North Atlantic,

post-Freudian distinction between somatic and psychic disorder

was found to have no local equivalent. Instead, all forms of

discomfort and misfortune were interpreted — on one level of

discourse, that is — in terms of affliction by supernatural

agents. Every person afflicted was supposed to have intermingling

ritual obligations towards various such agents (belonging to such

various classes as diseased kinsmen, minor land spirits, the Land

itself, and the pubol healing spirits). Some

ancestral obligations were inherited by birth, while others

stemmed from any number of contracts humans (the patient himself,

or a kinsman acting on his or her behalf) had once entered into

with these agents. Humans would always be behind in fulfilling

— in the way of paying for, and staging, expensive

sacrifices — their parts of the bargain, and illness was a

sign of the agent becoming impatient. To virtually all serious

complaints this aetiological system was applied, usually in

peaceful co-existence with cosmopolitan medicine as administered

either at home, at the migrants’ distant places of work, or

in the regional and national centres of Canchungo and Bissau.

This

unspecific aetiology could initially be studied on whatever

complaint my main informants happened to suffer from. However,

the project’s emphasis was on therapeutic effectiveness in

cases of mental disorder. Therefore, together with the

psychiatrist, I collected and analysed such local cases we could

find of what, by any cosmopolitan or transcultural-psychiatric

standards, would have be considered grave mental disorder.

On a

population of about 90,000 Manjaks today, severe mental cases

turned out to be rather rare (some of our best studied ones are

listed in table 1).

| patients |

name |

Fernando |

Carlos |

Arguetta |

Bajudessa |

Politia |

| sex |

male |

male |

female |

female |

female |

|

| year of birth |

1918 |

1953 |

1942 |

1957 |

1967 |

|

| year complaint became manifest |

1983 |

1972 |

1980 |

1982 |

1981 |

|

| residence |

is family head |

with F |

with MZS |

with paternal kin |

with F |

|

| complaint (provisional) |

psychotic |

chronic schizophrenia |

hysteria |

extreme apathy |

psychotic |

|

| anamnesis (selection) |

ex-napene,

junior partner took over practice; now

involved in modern Basic Health Care project |

war time separation from Mo;

extreme mobility aspirations imposed by F; rejected by

colonial patron when schooling in capital; still sexual

assaults on FW |

when a child, placed by F in

household of M’s ideal marriage partner; forced by F

to marry a non-Manjak in distant region of Guinea Bissau;

H and D died subsequently |

improper marriage; accompanied

migrant H to France; H long imprisoned there on criminal

charges; H failed to live up to kinship obligations

vis-à-vis both consang. and affinal kin at home |

F traditional ‘king’,

demoted in Independence struggle; extreme status loss in

family of orientation; patient could not stand

humiliation by schoolmates |

|

| cultic treatment |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| cosmopolitan psychiatric

treatment |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

Far from

corroborating my initial hypotheses as summarized above, this

material suggests that contemporary Manjak society, however much

it could be considered a backward labour reserve in the

capitalist world system, is characterized by a remarkably

wholesome balance, in its internal symbolic and authority

structure as well as in its relations with the outside world

(through migrancy combined with very strong and persisting ritual

ties with home). Gerontocratic relations appear to

prevent, rather than generate, insanity; and incipient

mental problems appear to be redressed and corrected in an early

stage, invariably by invoking a combination of local rituals

including the cult of the Land. The data indicate the therapeutic

effectiveness of this ritual complex. Severe mental

distress seems to occur or at least to persist primarily in such

cases when the subject is fundamentally incapable of

communicating effectively with the cult of the Land as mediated

by the elders.

I submit

that here we are hit upon the mainstay of Manjak medical culture.

Such blockage as appears to lead to persisting mental distress

always involves factors external to Manjak society, and in most

cases appears to consist in the disruption of the balance between

symbolic rootedness in Manjak society and (often prolonged and

distant) economic participation in the outside world —

typically one characterized by bureaucratic formal organizations,

urban structures and the capitalist mode of production (cf.

Collomb & Diop 1969; Diarra 1966). Manjaks fall mentally ill

if that outside society takes excessive control at the expense of

ties with home, the Manjak culture, and the central symbolic role

of the elders therein.

The

following example therefore appears to bring out the essence of

the therapeutic role of elders in Manjak society:

In her mother’s compound

Ndisia,[vii] a young woman of the Ucacenem

ward, awaited her migrant husband’s annual return from

Senegal. Alarmed by a series of earlier sudden infant deaths in

the family, she panicked at the first signs of fever and apathy

in her two-year old son Antonio, whom she was still

breast-feeding. Without delay she reached for the most powerful

healing strategy that Manjak culture provides: she took Antonio

to the house of the village’s most senior Land priest,

Fernando, to whom her family was not related and whose ward

(called Brissor) was in a different part of the village. She was

given a room in the priest’s men’s house,[viii] and stayed for over a week

until the boy showed definite signs of improvement. The old man

did not have to treat the child explicitly: his personal,

invisible emanations as an elder were considered to be eminently

effective. Through this action, moreover, Antonio gained lifelong

honorary membership of the elder’s ward, which even involved

the (in all other situations eagerly guarded and disputed) rights

of libation on the ward’s ancestral shrines.

Such therapeutic adoption, which does not affect the patient’s rights in his own ward of origin, is the only way in which libation rights can pass on to non-kin. In the neighbouring Vilela ward two young adult women had once gained similar rights under similar circumstances, and they regularly shared in collective rituals of the Brissor ward.

Part of

the underlying model is not difficult to reconstruct: illness is

seen as uprootedness, as a disrupted relationship between the

person and Land, and when the social and genealogical aspects of

this condition are redressed through fictitious re-affiliation,

the link with the Land is restored and improved, and the

Land’s life-giving force as mediated by the elder once more

flows freely to the patient.

All this

does not sound particularly original. If the Manjak socio-ritual

system had been consciously engineered by an anthropologist

familiar with the classical work of Meyer Fortes (1969a, 1969b),

the result may not have been too different from what I found

empirically. The most idealist, culture-centred symbolic analysis

might have arrived at the same sort of conclusion in terms of a

wholesome communion with the essence of a culture. Personally, I

would have distrusted this analysis for that very reason, —

as the all too predictable result of a set, neo-classical

interpretational framework. However, since my neo-Marxist

approach did give me ample opportunity to arrive at a materialist

interpretation if such had done more justice to the empirical

data, my ending up, instead, with the present, main-stream

interpretation reflects not so much the automatism of

time-honoured, dominant modes of anthropological analysis, but a

genuine struggle to get the most out of a rival, material

paradigm — and failing to do so.

However, trading a materialist

interpretation for a more symbolist one does not reveal to us the

underlying mechanism that in either case may be said to govern

the link between the individual on the one hand, and socio-ritual

structure on the other. The next question to be asked

is therefore: what, in the symbolic and/or material

structure of Manjak society, allows rituals controlled by senior

men to have such a strong impact on both mind and body?

I believe that the answer can be given, and that it lies not in

the sort of material structures that a political-economy approach

would reveal, but in the amazingly consistent Manjak system of

symbolism of the body, that, in a microcosm/macrocosm parallelism

reminiscent of various idealist philosophical systems in the

European tradition (Plotinus, Leibnitz), at the same time amounts

to a total conception of the world, in other words, of Land.

When I

tried to formulate, mainly on the basis of observation and

participation, Manjak notions of bodily and sensory functioning

and experience in health and disease, I was at first struck by an

extreme rigidity and reticence, which reminded me much more of

peasant culture in North Africa and civil society in Europe than

of any Black African traits such as I expected on the basis of

prolonged personal field-work in Zambia, anthropological studies,

and current North Atlantic and négritude stereotypes

concerning ‘the’ exuberant, utterly corporeal, rhythmic

and sensuous ‘African’. Among the Manjaks, it was as if

everything that could be socially and physiologically functional

and stimulating about the human body had become very highly

restricted. With the exception of children (up to non-initiated

young adults), Manjak villagers would hardly touch each other,

and would perform their digestive and sexual bodily functions in

the greatest secrecy so that not even the merest suggestion of

these needs or drives would enter into public life and

conversation. With averted gaze people would engage in series of

monologues rather than in dialogues; this would be true

particularly of the interaction of members of different

generations, but even age-mates would tend to fall into this

pattern. There was a little developed cuisine

whose products were meant to fill the stomach and drive home the

gender division of labour but hardly to cultivate (in the way of

food exchanges and collective meals) socio-ritual relations

beyond the extended family — except for rare occasions of

ritual commensality. The local music’s simple abstract

structure was wholly subservient to the abstract Morse-like

requirements of the talking drums. Representational arts appeared

to be absent, except the extremely stylized cylindrical wooden

sculptures that, as images of the deceased, constituted the

ancestral shrines. The most beautiful items Manjak culture

produced: band-woven cloths of intricate, abstract, multicoloured

designs, were not meant to be worn but to be hoarded in chests by

the dozen until the owner, at his or her dying day, would be sown

into them and thus committed to the grave; i.e. they were

displayed for a few minutes only, at the time that marked the

culmination of a human being’s life, and at the same time

his or her most intimate and consummative communion with the

Land: burial.

While

these few and disconnected impressions may suffice to indicate

the general restrained atmosphere of everyday life, in illness

behaviour a similar pattern seemed to be at work. Illness had to

be denied, dissimulated or repressed, both by the patient and by

his or her social environment. On the basis of illness, patients

could claim no dispensation from daily chores around the house

nor from the immensely heavy productive activities in the

paddy-fields. Any sick-bed was always a burden and never a

relief. As a result people were inclined to give in to their

‘weaknesses’ on this point only occasionally, with very

little social conform in the way of nursing, special privileges

etc., and then only for an amazingly short time. Being (publicly

acknowledged to be) ill was a state to be measured in hours

rather than in weeks or months.

In a

society so prone to migrancy to capitalist places of work, a

materialist anthropologist would be tempted to explore the extent

to which this rather unexpected pattern might be partly

attributed to the internalization of the ideology of capitalism.

Had not extreme commoditification, and exploitative labour

conditions under high capitalism, produced somewhat similar

notions of the human body and its ‘uses’, perhaps not

so much in the lives of suppressed workers but certainly in the

official codes of formal bureaucratic organizations within which

production was realized, in employers’ dreams and

aspirations, and in the standards applied by their company’s

doctors?

Further

research and reflection, however, convinced me that such an

interpretation is spurious. Manjak bodily symbolism is not in any

sense a product of capitalist encroachment, but on the contrary

is another manifestation of an all-pervading, integrated

cosmological system that, at best, protects

its bearers from the alienation inherent in the

peripheral-capitalist experience.

A

projection of current, enlightened notions of North Atlantic

culture would at first make the human body in Manjak culture

appear as extremely constrained, denied and repressed. But when

we go through the psychiatric case material, we find precious few

indications of such repression in the mental symptoms of

patients.

Instead,

the fundamental underlying cultural image seems to be that of the

Perfect Body, which is whole and fertile, which is

closed onto itself to such an extent that It no longer has

orifices; that no longer has needs that necessitate the passing

of external substances from outside to inside (or even from

inside to outside); and that by virtue of this perfection places

Itself outside the chain of human and social exchange, dependence

and manipulation, and at the apex of filiation. Mental

distress means separation from that Perfect Body; mental health

means emulating that Perfect Body, and anxiously but

whole-heartedly concealing the extent to which one’s own

body and social functioning emulates that ideal only imperfectly.

Among

the living, the male elder comes closest to this ideal. Although

he may not be beyond the consumption of food and drink, his

consumption is largely confined to the inner recesses of the

house and of the Sacred Grove, shielded from the common gaze. His

bodily needs are thus denied, and he cannot allow himself to be

ill. If still involved in chains of social and bodily exchange,

it is others that need to receive from him (rice, cattle, sperm,

acceptance, healing etc.), and never the other way round. His

being is whole and closed (closed also from the stream of

information and gossip — Manjak secretiveness perfectly fits

this model). His body is almost lifted above its human

limitations, and therefore — as long as no publicly

witnessed passage across orifices is at hand — can be

allowed to be massively displayed in a mere loin-cloth.

Young

men, women and children are way beneath this ideal, and therefore

may indulge, in varying degrees, in all the imperfections of the

human and social condition: devour, defecate, mate, receive,

adorn, beg, steal, be entirely naked, disclose secrets, etc.

Again

one step above the elder is the ancestor, so close to the Ideal

Body that he or she may be represented by a mere short stick

protruding from the ground: the standard ancestral shrines as

referred to above; although locally recognized as an

anthropomorphic image, not even facial openings are cut, and only

a slight suggestion is given of a neck or a reclining

shoulder-line. Like an elder, and even more so, the ancestor is

outside a chain of exchange, can no longer ask and need not ask,

since his or her living descendants are supposed to do everything

they can to anticipate his desires and fulfil their obligations

— hence their embarrassment and shame when illness (always

interpreted as sign of a breach of contractual obligations

vis-à-vis a superior being) publicly reveals that they have

failed to do so.

But the

Ultimate Body that incarnates this system of symbolism and

carries it to its final consequence is Land Itself. The universal

source of life, also in the material sense of rice and palm-wine,

it may give[ix] but it cannot be admitted to receive.

Humans may try to impose upon Land with their gifts (when pouring

alcoholic drinks and animal blood) and with their dead bodies

(which are buried in the Land), but Land has no orifices through

which to receive. Its shrines are inconspicuous, without

elaboration. They may be marked by a shrub, a piece of tree

trunk, but often are just a totally unmarked spot; and they

particularly lack formal libation basins — the equivalents

of bodily orifices; at best, in the course of a ritual, shortly

before libation takes place, the officiant may with a quick

movement of his hand sweep open a very shallow hole of only one

or two centimetres deep and a few decimetres wide, discarding any

dead leaves that may have collected there. Alternatively, graves

(Land’s only undeniable openings) can only be dug by senior

Land priests, who force ordinary mourners to look chastely away

when the body — already rendered orifice-less in its thick,

mummy-shaped layer of cloths — is lowered into the ground,

and who through secret underground extensions of the grave

attempt to conceal its exact location forever after...

To an

amazing extent and degree of detail can both the ritual and the

medical system of the Manjaks be subsumed under the formula of

the orifice-less Perfect Body, right up to

the form and content of Land ritual and the material shape of

Land shrines. Without exaggeration, the human body can

be said to be the dominant symbol in Manjak culture, and it has

been applied and transformed in such a consistent way as to

— surpass and surmount everything corporeal. Of

course the relationships involved are not always those of direct

transposition. For instance, in many aspects of Manjak symbolism

the topological inverse of the human bodily shape is encountered:

a hollow, tapering cylindrical space, and

modern glass bottles, that happen to fit this description rather

well, are among the most conspicuous material items in Manjak

ritual and everyday life — dominating conversations and

actions to an incredible extent.

Confronted

with such circularity between mind and body, macrocosm and

microcosms, one can only guess at the psycho-somatic implications

of a cosmology that presents the human body, with its constant

flow in and out of natural, corporeal and social matter, as the

imperfect incarnation of the perfectly closed, life-giving Land,

the principal deity of this society. One suspects possibilities

of symbolic and corporeal transfer and transposition in which

symptom and economic action, exchange and well-being merge to an

extent that may well be deemed capable of eluding anything but

the most brutal confrontation with the logic of capitalism.

Whether this symbolic system in itself has been the principal

factor in keeping capitalism out, or whether, alternatively, the

overall nature of the political economy of this part of the

African Atlantic coast has merely facilitated the emergence and

persistence of this symbolic system, remains a question for

further research.

Meanwhile, the cultic complex of the napenes,

their pubols and their rituals occupy a

curious position in this set-up. It combines selected elements of

the overall idiom but mainly transforming them into their

opposites. Here we find, in flagrant contrast with the cult of

the Land proper, elaborate, thick-walled womb-like

shrines, packed with myriad paraphernalia and including

conspicuous libation basins; the latter tend to occur in pairs

and then particularly suggest a topological inversion of human

breasts. The supernatural which, in its corporeal

sublimation, is so unapproachable, forbidding and masculine in

the other manifestations of this cosmology, here suddenly appears

as approachable, bodily, and maternal. It is

here, in the pubols’ divination and

ritual, that mortals can yet attempt to have direct communion

with the Land: through the sacrificial smudge

that the priest, with bare hands, smears

directly onto the client’s naked skin

— an almost shocking corporality, therapeutically very

effective as if to offset the detached, ascetic abstractions of

the cultic main stream. Here, in this cultic side-stream, one yet

seeks to manipulate, and to set condition to, the Land’s

formidable powers. A poor men’s version, one would be

inclined to say, of the exalted ideals of the dominant cult,

— a distorting mirror of its aspirations and negations, and

as such the aspect of Manjak ritual that could and does lend

itself best for ritual entrepreneurship and innovation. Here

client’s expenses are of a level comparable to that of the

ancestral and Land cult — but they are seen not as

fulfilment of unconditional obligations but as payments, and in

addition to prestations in kind involve considerable amounts of

money. The aetiological repertoire of the pubol

attendants is no longer unspecific and general, but specifies

particular complaints and their specific, elaborate remedies,

whose forms and interpretations are subject to healer’s

constant innovations and re-interpretations in an attempt to

capture an uncertain and highly competitive medico-ritual local

market. The relation between healer and patient is no longer cast

in the idiom of belonging to and venerating the same local Land

(although the Land cult does claim its share from every

transaction going on in the pubols) to which

one is attached by birth without optionality or escape, but in

the idiom of contract. In other words, at the oracular shrines we

encounter a type of transformation (of the dominant Manjak

symbolic idiom) that is not only feminine, routinized and eroded

— it also begins to develop the well-known traits

of commoditification, constituting the locus of capitalist

encroachment in this otherwise fairly impenetrable socio-ritual

system.

Little

wonder perhaps, that this is the aspect of the Manjak ritual

scene that accommodated me (myself steeped in an utterly

commoditified, capitalist life-world) more than any other, to

which I could relate most — which even appeared to offer

partial but eminently effective answers to my own existential

needs.

But here

we are operating at the very fringe of the Manjak socio-ritual

and medical system. Reference to capitalism does not begin to

explain the patterns of symbolism, continuing gerontocracy,

migrant participation, and therapeutic effectiveness that

constitute the core of Manjak society. But why should a

Marxist-inspired approach to religion confine itself to the

capitalist mode of production? A closer look at the

non-capitalist relations of production on which Manjak village

society continues to revolve, may suggest alternative ways to yet

break away from the fixation on cosmology and ideology, and lay

bare the patterns of economic action, and exploitation, that are

really at work. Are not the youth, through their expensive ritual

participation, investing in the sort of

ideological capital that, one day, when they have become elders

themselves, they may claim to be theirs? Are not the elders

transmuting capitalist-derived capital into Manjak capital,

laundering (much like, in North Atlantic society, money

proceeding from tax evasion and crime) the proceeds from labour

migration that otherwise would remain utterly devoid of meaning

and value even for the young migrants themselves? Rather than

conceiving of the body as Land, could we not try to reverse to

equation and spell out what it means — both symbolically and

economically — that the human body, locus of productive

force by excellence, is symbolically externalized, slighted and

denied?

When a

non-capitalist society scarcely seems to yield to capitalist

encroachment, it is tempting to resort to a neo-classical,

idealist interpretation — thus reconstructing and making

explicit what is implied in the local ideology. But in the long

run it would be more rewarding to seek and formulate a specific

political economy that is cut to the measure of that society. In

this vein Peter Worsley (1956) reinterpreted Tallensi society as

analysed by Fortes. As far as Manjak society is concerned,

however, that part of my task only begins to be discernible now.

Carriera, A.A.P.

1947a

Vida social dos Manjacos. Bissau: Centro de Estudios da Guiné.

1947b

Céu, Deus e a Terra (lenda de Manjacos). Boletim Cultural da

Guiné Portuguesa (Bissau), 2:461-463.

1961

Símbolos, ritualistas a ritualismos animo-feiticistas na Guiné

Portuguesa. Boletim Cultural da Guiné Portuguesa (Bissau) 16,

63: 505-540.

Collomb, H., & B. Diop

1969

Migration urbaine et santé mentale. Waltham (Mass.): African

Studies Association.

Davidson, B.

1981

No fist is big enough to hide the sky: The liberation of

Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde, London: Zed Press; second edition

of: The liberation of Guiné, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1969.

de Jong, J.T.V.M.

1987

A descent into African psychiatry. Amsterdam: Royal Tropical

Institute.

Diarra, S.

1966

Problèmes d’adaptation de travailleurs africains noirs en

France. Psychopathologie africaine, 2: 107-126.

Droogers, A.

1985

From waste-making to recycling: A plea for an eclectic use of

models in the study of religious change. In:

W.M.J. van Binsbergen & J.M. Schoffeleers (eds.), Theoretical

explorations in African religion, London/Boston: Kegan Paul

International, pp. 101-137.

Fortes, M.

1969a

The dynamics of clanship among the Tallensi. Oosterhout (The

Netherlands): Anthropological Publications, and London: Oxford

University Press. Reprint of the 1945 edition.

1969b

The web of kinship among the Tallensi. Oosterhout (The

Netherlands): Anthropological Publications, and London: Oxford

University Press. Reprint of the 1949 edition.

Meillassoux, C.

1975

Femmes, greniers et capitaux. Paris: Maspero.

Rey, P.-P.

1971

Colonialisme, néo-colonialisme et transition au capitalisme:

Example du ‘Comilog’ au Congo-Brazzaville, Paris:

Maspero.

1973

Les alliances de classes, Paris: Maspero.

1979

Class contradiction in lineage societies. Critique of

Anthropology, 13-14: 41-60.

van Binsbergen, W.M.J.

1979

The infancy of Edward Shelonga: An extended case from the Zambian

Nkoya. In: J.D.M. van der Geest & K.W.

van der Veen (eds), In search of health: Six essays in medical

anthropology. Amsterdam: Anthropological Sociological Centre, pp.

19-90.

1981a

Religious change in Zambia, London/Boston: Kegan Paul

International.

1981b

Theoretical and experiential dimensions in the study of the

ancestral cult among the Zambian Nkoya. Paper read at the

symposium on Plurality in Religion, International Union of

Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences Intercongress,

Amsterdam.

1984a

Can anthropology become the theory of peripheral class struggle?:

Reflexions on the work of P.P. Rey. In:

W.M.J. van Binsbergen & G.S.C.M. Hesseling, Aspecten van

staat en maatschappij in Afrika: Recent Dutch and Belgian

research on the African state, Leiden: African Studies Centre,

pp. 163-180.

1984b

Socio-ritual structures and modern migration among the Manjak of

Guinea-Bissau: Ideological reproduction in a context of

peripheral capitalism. Antropologische Verkenningen (Utrecht), 3,

2: 11-43.

1985a

From tribe to ethnicity in western Zambia. In:

W.M.J. van Binsbergen & P.L. Geschiere (eds.), Old modes of

production and capitalist encroachment, London/ Boston: Kegan

Paul International, pp. 181-234.

1985b

The cult of saints in north-western Tunisia: An analysis of

contemporary pilgrimage structures. In E.

Gellner (ed.), Islamic dilemmas: Reformers, nationalists and

industrialization, Berlin/New York/Amsterdam: Mouton, pp.

199-239.

van Binsbergen, W.M.J., & P.L.

Geschiere

1985

Marxist theory and anthropological practice. In

W.M.J. van Binsbergen & P.L. Geschiere (eds.), Old modes of

production and capitalist encroachment, London/ Boston: Kegan

Paul International, pp. 235-89.

van Binsbergen, W.M.J., & J.M.

Schoffeleers (eds.)

1985a

Theoretical explorations in African religion. London/Boston:

Kegan Paul International.

Worsley, P.

1956

The kinship system of the Tallensi: A revaluation. Journal of the

Royal Anthropological Institute 86, I: 37-75.

[i] After preparatory trips in 1981 and 1982, field-work was conducted in 1983 in the Calequisse section of the Cacheu region, with occasional extensions to the Caió and Coboiana sections. I am indebted to the people of the Cacheu region for their hospitality and interest; to the African Studies Centre, Leiden, for financing the project and granting me leave of absence; to Joop de Jong, then Head of Psychiatry, 3 de Agosto Hospital, Bissau, for initiating the project and contributing to its more specifically psychiatric side; to the Ministry of Health, Guinea Bissau, for facilitating administrative and logistic aspects; to Patricia Saegerman and Else Broers, as wife and elder sister respectively perceptive companions in the field; and finally to Renaat Devisch, whose penetrating discussions in the stimulating environment of the Louvain ‘Unit of Symbol and Symptom’, 1984 and 1985, greatly contributed to my analysis of Manjak symbolism. The first version of this paper was read at the Second Satterthwaite Colloquium on African Religion and Ritual, Satterthwaite (Cumbria), U.K., April 1986; I am indebted to Kirsten Alnaes, Michael Bourdillon, Richard Fardon, Ronald Frankenberg, Ladislav Holy, Richard Werbner and James Woodburn for stimulating comments on that occasion. A revised version was read at the Institut für Ethnologie, Freie Universität, Berlin (West), May 1986, where I benefited from stimulating comments made by Georg Elwert, Till Förster, Georg Pfeffer and Helmut Zinser. This article was originally published in English as: ‘The land as body: An essay on the interpretation of ritual among the Manjaks of Guinea-Bissau’, in: R. Frankenberg (ed.), Gramsci, Marxism, and Phenomenology: Essays for the development of critical medical anthropology, special issue of Medical Anthropological Quarterly, new series, 2, 4, December 1988, p. 386-401.

[ii] Cf. van Binsbergen 1984a and references cited there.

[iii] I have pursued a materialist approach for a number of years (cf. van Binsbergen 1981a; van Binsbergen & Geschiere 1985; more specifically in the medical anthropological field: 1979 and 1981a: ch. 5, 6 and 7). I have repeatedly confessed my guilty conscience (1981a: 10f, 73f; 1981b, 1984a, 1985a), and stressed the need for a synthesis of Marxian ideas and the sophisticated insights of main-stream symbolic anthropology (1981a: 68f; van Binsbergen & Schoffeleers 1985).

[iv] Van Binsbergen 1985b and other works cited there; however, the possibility of a materialist perspective was indicated in van Binsbergen & Geschiere 1985.

[v] Cf. Carreira 1947a, 1947b, 1961. De Jong 1987 also discusses general religious and medical concepts partly derived from Manjak culture, although most of his specific descriptions derive from other parts of Guinea-Bissau.

[vi]

Meillassoux 1975; Rey 1971, 1973, 1979; cf. van Binsbergen &

Geschiere 1985.

[vii] All proper names are pseudonyms.

[viii] Visiting daughters of the house are also put up here (and not at the women's house) when the occasion arises.

[ix]

Although not through orifices: the Land gives (i.e. yields produce)

not in highly localized spots but over extensive land areas:

paddy-fields, palm and cashew groves, and gardens. Significantly,

the tapping of palm trees and the resulting palm wine (ideally

set aside for consumption by elders in a ritual context) had a

mystical significance of communicating with the essence of Land.

| page last modified: 11-02-01 14:26:41 |  |

|||

|