|

Rethinking

Africa’s transcontinental continuities in pre- and

protohistory

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE

African Studies Centre, Leiden University

Leiden, the Netherlands

12-13 April 2012

organising committee Marieke van Winden, Gitty Petit

& Wim van Binsbergen

funding: African Studies Centre, Leiden (ASC) and Leiden

University Foundation (LUF)

for ALL

conference details, please contact Marieke van Winden (WINDEN@ascleiden.nl )

|

|

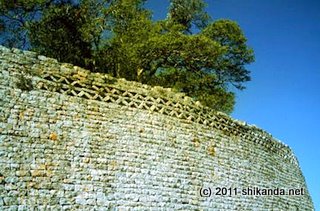

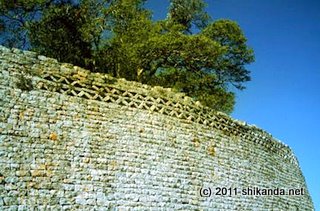

The Great Enclosure of the Great

Zimbabwe complex, one of the most

contested sites in the study of Africa’s

transcontinental continuities in

pre- and protohistory |

this conference

is to mark Wim van Binsbergen’s retirement from the African Studies Centre,

Leiden, after 35 years

OBSERVERS. Specialists, interested

non-specialists, and all people associated with Wim van

Binsbergen in the course of his career are welcome to

attend the first day of the conference with observer

status (attendance fee EUR25). Considering the expected

massive interest it is important to register beforehand.

Please contact Marieke van Winden (WINDEN@ascleiden.nl

) for details.

|

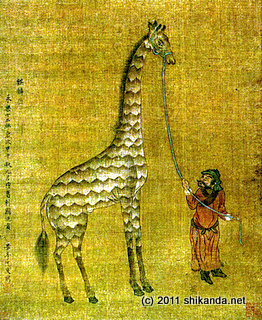

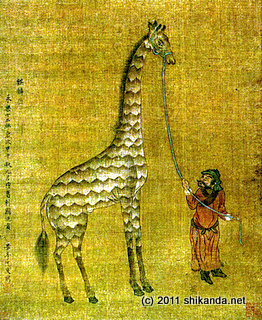

a contemporary Chinese depiction of a

giraffe presented to the Chinese

emperor in the context of Admiral

Zheng He's voyages,

early Zheng He's voyages,

early

15th c. CE |

return to: Topicalities page | Shikanda portal index

3. DETAILS ON

TRAVEL ARRANGEMENTS, as per 15 March 2012

(no longer

of any relevance)

4. CLICK

HERE FOR THE FINAL CONFERENCE PROGRAMME AS PER 10 APRIL 2012

(PDF)

5. CLICK HERE FOR A SELECTION OF CONFERENCE PHOTOGRAPHS

6. LIST OF ACCEPTED

TITLES AND ABSTRACTS, as per 15 March 2012; LOGIN ACCESS TO DRAFT

PAPERS

please note:

Whereas titles and abstracts of the conference papers are open to

the general public, for obvious reasons (copyright, the papers'

provisional state) we have restricted access to the draft papers

themselves to conference participants and observers. Those

qualifying have been issued with a specific Username and

Password, with which to open the following key so as to gain

access to webpage containing the conference papers, in the same

order as in which titles and abstracts are listed below.

Anselin, Alain

In search of the sketch of an

early African pool of cultures as homeland from which the

pre-dynastic Egypt came to light.

Editor

in chief of the peer reviewed journal The Cahiers Caribéens

d’Egyptologie and the electronic papyrus i-Medjat

Referring to the

historical mapping of the African populations inside the light of

genetics studies, and taking into account recent archaeology of

Upper Egypt and its wider Saharan and Sudanese hinterland, this

paper outlines the geographical location and movements of early

peoples in and around the Nile Valley. So, primarily linguistic

resources are used in this view for comparative studies of natural

phenomena names, and that of the material culture, as

worship places or key-artifacts in Ancient Egyptian and

contemporary African cultures, are sketched out. The paper

pursues by a comparative overview of the immaterial culture by

the way of a short but basic conceptual vocabulary shared

by the contemporary Chadic-speakers, Cushitic-speakers peoples

and contemporary Nilo-Saharanspeakers within Ancient

Egyptian-speakers one. This cultural and linguistic

enlightenments suggest firstly that ancestors of these peoples

were able to share in ancient times a common cultural homeland -

perhaps a saharo-nubian area of ethnic and linguistic contact and

compression; and secondly that the earliest speakers of the

Egyptian language could be located to the south of Upper Egypt

or, earlier, in the Sahara. As a matter of fact, the marked

grammatical and lexicographic affinities of Ancient Egyptian with

Chadic languages are well-known, and consistent Nilotic cultural,

religious and political patterns are detectable in the formation

of the first Egyptian kingships. The question all these data

raise is the historical and sociological articulation between the

languages and the cultural patterns of this pool of ancient

African societies from which emerged Pre-dynastic Egypt.

Berezkin, Yuri

Prehistoric cultural diffusion

reflected in distribution of some folklore motifs in Africa

Though the very

first human myths were probably created in Africa and brought to

other continents with the "Out-of-Africa" migration of

early Homo sapiens, many, if not most of the stories recorded in

Tropical Africa by missionaries, ethnologists and linguists can

have Eurasian and not African roots. In some of such stories

animals like sheep, goat and dog play crucial role and because

these species were domesticated in Eurasia and spread into Africa

rather late the African origin of the stories themselves is also

under doubt. I mean first of all some versions of the

"muddled message" and interpretation of the stars of

Orion as a hunting scene. Another large set of stories is related

to fairy-tales and have extensive parallels in Eurasia. The

existence of North American (though not South American) cases

means that the plots in question were known in Eurasia at least

12-15 millennia B.P. The complete lack of Australian cases means

that these stories were hardly known to the early modern humans.

Both Eurasian and African origin is possible for these stories

but the former is more plausible. The Eurasian parallels are more

numerous in West Africa where the myths that most probably have

African origin are just rare. Some animal stories unite Africa

and Europe being unknown anywhere else (a hare or a bird who

refused to dig with the others a well or a river is an example).

Here the direction of the diffusion is unclear. All the plots

that I write about have wide distribution in Tropical Africa and

hardly could spread recently thanks to the modern European

influence. If we "delete" possible Eurasian influence

in Tropical African folklore, we would get an idea of what the

worldview of local hunter-gatherers could be before spread of

productive economy and emergence of trade connections with North

African and Near Eastern societies.

Blažek, Václav

Afroasiatic migrations: Linguistic evidence

The

Afroasiatic migrations can be divided into historical and

prehistorical. The linguistic evidence of the historical

migrations is usually based on epigraphic or literary witnesses.

The migrations without epigraphic or textual evidence can be

linguistically determined only indirectly, on the basis of

ecological and cultural lexicon and mutual borrowings from and

into substrata, adstrata and superstrata. Very useful is a

detailed genetic classification, ideally with an absolute

chronology of sequential divergencies. Without literary documents

and absolute chronology of loans the only tool is the method

called glottochronology. Although in its

‘classical’ form formulated by Swadesh it was

discredited, its recalibrated modification developed by Sergei

Starostin gives much more realistic estimations. For Afroasiatic

G. Starostin and A. Militarev obtained almost the same

tree-diagram, although they operated with 50- and 100-word-lists

respectively.

Afroasiatic

(S = G. Starostin 2010; M = A.

Militarev 2005)

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

internal

|

| |

-9500

|

-8500

|

-7500

|

-6500

|

-5500

|

divergence

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Omotic |

| |

-14

760S |

|

|

|

|

(-6.96S/-5.36M)

|

| |

|

|

-7

870M

|

|

|

|

Cushitic |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(-6.54S/-6.51M)

|

Afroasiatic

|

-10

010S |

|

|

|

Semitic |

|

-9

970M |

|

|

|

|

(-3.80S/-4.51M)

|

|

|

-7

710S

|

|

|

|

Egyptian |

| |

|

-8

960M

|

|

|

|

|

(Middle:

-1.55)

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Berber |

| |

|

|

-7250S

|

|

-5

990S

|

|

(-1.48S/-1.11M)

|

| |

|

|

-7710M

|

-5

890M

|

|

Chadic |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

(-5.13S/-5.41M)

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rather

problematic results for Omotic should be ascribed to extremely

strong influences of substrata. Various influences, especially

Nilo-Saharan, are also apparent in Cushitic, plus Khoisan and

Bantu in Dahalo and South Cushitic. Less apparent, but

identifiable, is the Nilo-Saharan influence in Egyptian (Takács

1999, 38-46) and Berber (Militarev 1991, 248-65); stronger in

Chadic are influences of Saharan from the East (Jungraithmayr

1989), Songhai from the West (Zima 1990), plus Niger-Congo from

the South (Gerhardt 1983).

To

map the early Afroasiatic migrations, it is necessary to localize

in space and time the Afroasiatic homeland. The assumed

locations correlate with the areas of individual branches:

Cushitic/Omotic:

North Sudan, Ethiopia and Eritrea between the Nile-Atbara and Red

Sea - Ehret (1979, 165); similarly Fleming (2006, 152-57), Blench

(2006). Hudson (1978, 74-75) sees in Greater Ethiopia a homeland

of both Afroasiatic and Semitic.

Area

between Cushitic & Omotic, Egyptian, Berber and Chadic:

Southeast Sahara between Darfur in Sudan and the Tibesti Massiv

in North Chad - Diakonoff 1988, 23.

Chadic:

North shores of Lake Chad - Jungraithmayr 1991, 78-80.

Berber-Libyan:

North African Mediterranean coast - Fellman 1991-93, 57.

Egyptian:

Upper Egypt - Takács 1999, 47.

Semitic:

Levant – Militarev 1996, 13-32. This solution is seriously

discussed by Diakonoff (1988, 24-25) and Petrácek (1988, 130-31)

as alternative to the African location.

These

arguments speak for the Levantine location:

Distant

relationship of Afroasiatic with Kartvelian, Dravidian,

Indo-European and other Eurasiatic language families within the

framework of the Nostratic hypothesis (Illic-Svityc 1971-84;

Blažek 2002; Dolgopolsky 2008; Bomhard 2008).

Lexical

parallels connecting Afroasiatic with Near Eastern languages

which cannot be explained from Semitic: (i) Sumerian-Afroasiatic

lexical parallels indicating an Afroasiatic substratum in

Sumerian (Militarev 1995). (ii) Elamite-Afroasiatic lexical and

grammatical cognates explainable as a common heritage

(Blažek 1999). (iii) North Caucasian-Afroasiatic parallels

in cultural lexicon explainable by old neighborhood (Militarev,

Starostin 1984).

Regarding

the tree-diagram above, the hypothetical scenario of

disintegration of Afroasiatic and following migrations should

operate with two asynchronic migrations from the Levantine

homeland: Cushitic (& Omotic?) separated first c.

12 mill. BP (late Natufian) and spread into the Arabian

Peninsula; next Egyptian, Berber and Chadic split from Semitic

(the latter remaining in the Levant) c. 11-10 mill. BP and

they dispersed into the Nile Delta and Valley.

The

present scenario has its analogy in the spread of Semitic

languages into Africa. The northern route through Sinai brought

Aramaic and Arabic, the southern route through Bab el-Mandeb

brought Ethio-Semitic.

References

Blažek,

Václav. 1999. Elam: a bridge between Ancient Near East and

Dravidian India? In: Archaeology and Language IV. Language

Change and Cultural Transformation, eds. Roger Blench &

Matthew Spriggs. London & New York: Routledge, 48-78.

Blažek,

Václav. 2002. Some New Dravidian - Afroasiatic Parallels. Mother

Tongue 7, 171-199.

Blench,

Roger. 2006. Archaeology, Language, and the African Past.

Oxford: AltaMira.

Bomhard,

Allan R. 2008. Reconstructing Proto-Nostratic: Comparative

Phonology, Morphology, and Vocabulary, I-II. Leiden-Boston:

Brill.

Diakonoff,

Igor M. 1988. Afrasian languages. Moscow: Nauka.

Dolgopolsky,

Aaron. 2008. Nostratic Dictionary. Cambridge:

<http://www.dspace.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/196512>

Ehret,

Christopher. 1979. On the antiquity of agriculture in Ethiopia. Journal

of African History 20, 161-177.

Fellman,

Jack. 1991-93. Linguistics as an instrument of pre-history: the

home of proto Afro-Asiatic. Orbis 36, 56-58.

Fleming,

Harold C. 2006. Ongota. A Decisive Language in African

Prehistory. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Gerhardt,

Ludwig. 1983. Lexical interferences in the Chadic/Benue-Congo

border area. In: Studies in Chadic and Afroasiatic linguistics,

ed. by Ekkehard Wolff, Hilke Meyer-Bahlburg. Hamburg: Buske,

301-310.

Hudson,

Grover. 1978. Geolinguistic evidence for Ethiopian Semitic

prehistory. Abbay 9, 71-85.

Illic-Svityc,

Vladislav. 1971-84. Opyt sravnenija nostraticeskix jazykov,

I-III. Moskva: Nauka.

Jungraithmayr,

Herrmann. 1991. Centre and periphery: Chadic linguistic evidence

and its possible historical significance. Orientalia

Varsoviensia 2: Unwritten Testimonies of the African Past.

Proceedings of the International Symposium (Warsaw, Nov

1989), ed. by S. Pilaszewicz, E. Rzewuski. Warsaw: Wydawnictwa

Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 61-82.

Militarev,

Aleksandr. 1991. Istoriceskaja fonetika i leksika

livijsko-guancskix jazykov. In: Afrazijskie jazyki 2.

Moskva: Nauka, 238-267.

Militarev,

Aleksandr. 1995. Šumery i afrazijcy. Vestnik drevnej

istorii 1995/2, 113-127.

Militarev,

Alexander. 1996. Home for Afrasian: African or Asian? Areal

Linguistic Arguments. In: Cushitic and Omotic Languages.

Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium (Berlin, March

1994), ed. bz C. Griefenow-Mewis, R.M. Voigt. Köln: Köppe,

13-32.

Militarev,

Alexander. 2005. Once more about glottochronology and the

comparative method: the Omotic-Afrasian case. In: Orientalia

et Classica VI: Aspekty komparatistiki, 339-408.

Militarev,

Aleksandr, Starostin, Sergei. 1984. Obšcaja

afrazijsko-severnokavkazskaja kul’turnaja leksika. In: Lingvisticeskaja

rekonstrukcija i drevnejšaja istorija Vostoka 3: Jazykovaja

situacija v Perednej Azii v X-IV tysjaciletijax do n.e.

Moskva: Nauka, 34-43.

Petrácek,

Karel. 1988. Altägyptisch, Hamitosemitisch und ihre

Beziehungen zu einigen Sprachfamilien in Afrika und Asien. Praha:

Univerzita Karlova.

Starostin,

George. 2010. Glottochronological classification of Afroasiatic

languages. Ms.

Takács,

Gábor. 1999. Etymological Dictionary of Egyptian, Vol. I:

A Phonological Introduction. Leiden-Boston-Köln: Brill.

Zima,

Petr. 1990. Songhay and Chadic in the West African Context. In:

Proceedings of the Fifth International Congress (Vienna, Sept

1987), Vol. 1, ed. by Hans Mukarovsky. Wien: Afro-Pub, 261-274.

Coquery-Vidrovitch, Cathérine

Rethinking Africa’s

Transcontinental continuities

Professeur

émérite, Université Paris Diderot Paris-7

This paper intends

to demonstrate, by the way of an historical overview of

Africa’s centrality from the beginnings of mankind, that all

over successive historical globalisations, Africa South of the

Sahara (we may roughly take it as a geographical subcontinent)

was no more no less than other “worlds” (Indian

Ocean world, Mediterranean world, Far East Asia, Europe, etc.) at

the centre of the other worlds. Europeans have built

“their” idea of Africa, which they believed and still

believe they had “discovered”, while they were by large

the last ones to do so. Africa and Africans developed a long

history before Europeans interfered. Moreover, they played

a prominent role at different stages of world globalization

before Western intervention.

Needless to remind

that mankind began in Africa and diffused from Africa all over

the world.

Geographically,

Africa is located at the core of three worlds. Africa allowed

them to be connected one with the other: the Mediterranean world

(from Ancient times), the Indian Ocean World, and (quite later)

the Atlantic world.

Therefore, from the

beginning of Ancient history, Africa played a major worldwide

role:

-

Africa was for long the major provider of gold, either to the

Indian Ocean world (from Zimbabwe), as to the Mediterranean and

European world (from western sudan). It was already known by

Herodotus (fifth century BC) and was superseded only in the 18th

century when gold began to be imported from Brazil. African gold

was a major incentive to help develop the rest of the world. Of

course Africans did not know it, but African gold, transmitted to

Europe by the Arabs, financed Marco Polo’s travel to China

in the 13th century. African gold payed for the

Portuguese fleet in the fifteenth century, and for the creation

of the first sugar plantations in Canaries islands, Saõ Tome

then Brazil.

-

Africa was a major world provider of force of labor, sending

slaves to the rest of the world, as well to the Muslim world, to

India, as to the Americas. Plantations, whose economic importance

was prominent in the premodern era, were possible only thanks to

African manpower

-

With the industrial Revolution, Africa was a major provider of

raw materials for British and French growing industrialisation:

tropical vegetal oil seeds and tinted wood conditioned

lightening, oiling of machines and textile industry all over the

nineteenth century, as long as electricity and chemical dyes did

not yet exist. It went on with rubber, coffee and cocoa at the

turn of the twentieth century

-

Useless to remind that today, Africa is a leader in sources of

energy (gas) and precious minerals again. South African gold

renewed with the ancient gold streams, providing 60percent of the

gold in the world (80percent of the western gold after the soviet

revolution)

The

question is not so much to demonstrate it, which might (and

should) be relatively well known, but to understand why these

evidences were let aside, forgotten, or even denied. Of course we

may (negatively) assert that others confiscated African gold,

African men and African raw materials. But it may be as

instructive to (positively) look at the process by which Africa

afforded so many wealth and products without which other

continents could not develop. Africa was necessary to world

development and Africans were actors and unceasingly adapting

partners to be studied as such, and not to be just reduced to

passive victims (no more no less than others, for other reasons;

plantations could not develop without planters, but also without

slaves; industry could not develop without industrial discoveries

and steam machines, but it could not produce without African raw

materials).

Why

was it denied only for Africa, which was just made a

“periphery” by the will of Western knowledge as early

as European believed to have “discovered” Africa? Let

us rather say that Africans “discovered” Europeans,

long after they had already met Arabs, Indians, and even Chinese.

Africa was not marginal to capitalism: like others, it was a

major condition for world development, i.e. for the making of

capitalism.

Dick-Read, Robert

Pre-Islamic Indonesian contacts

with sub-Saharan Africa

It is an

undisputed fact that at some stage in the distant past

Austronesian-speaking mariners from the Indonesian islands

crossed the Indian Ocean to Africa and Madagascar.

But this poses

many questions: Was this crossing a single event? Or were there

ongoing crossings over many years … even centuries? Did

these mariners settle in Africa? If so, where? How far inland did

they penetrate? In what ways, if any, did they influence the

cultures of Africa? Precisely who were the Indonesian mariners

who came to Africa? Why did they come? Were they driven by

opportunities to trade … or was there some basic urge to

explore the unknown as must have been the case with their

brethren in the Pacific? Was their interest restricted to the

East coast of Africa? Or did they sail round the Cape and up to

the Bight of Benin and beyond? How did the settlement of

Madagascar feature in this geographic puzzle? What was the

relationship between Austronesian-speaking Madagascar and

mainland Africa?

This paper

endeavours to answer these questions on the strength of the

available evidence, with particular focus on the Zanj of East

Africa, and evidence of Indonesian influences in Western Africa

including a speculative flurry as to how Mahayana Buddhists of

SEA may have left their mark on important aspects of Nigerian

culture.

Ehret, Christopher

Matrilineal descent and the

gendering of authority: What does African history have to tell

us?

There has long

been a widespread historical and anthropological idea that, up

till very recent times, women everywhere—whatever the kin

structure of their society—were always, in the last

analysis, under the authority of the men of their society. Whether

in societies with matrilineal or patrilineal descent,

women’s position was the same. Under patriliny the

husband has that authority; under matriliny, the mother’s

brother. But is that universally true? The vast

majority of historians come from and write on societies, from

China and Japan in the east to Europe in the west, characterized

by long histories of often outright patriarchy. Male

dominance tends to be woven into the understandings that

historians grow up with and confront in their personal lives.

But what if we shift our historical attention to regions outside

the long “middle belt” of the Eastern Hemisphere?

Does matriliny equally entail male dominance over the course of

time, or might matriliny have significantly different

consequences for the roles of women in history? Two very

long-term histories from widely separated parts of the African

continent offer arresting perspectives on this issue. One

of these histories involves the peoples of the southeastern

regions of central Africa; the other, the ancient societies of

the northern Middle Nile Basin.

Hromník, Cyril A.

Stone Structures in the

Moordenaars Karoo: Boere or “Khoisan” Schanzes

or Quena Temples?

Historian/Reseacher,

INDO-AFRICA, Rondebosch, South Africa.

Just after midnight on the 15th of September 2006,

this historian, ETV crew, a journalist, a number of interested

academics from the University of Stellenbosch, a government

minister and several interested laymen together with the farm

owner Mr. David Luscombe and his and my sons gathered on the

summit of a small rantjie (little ridge) in the

Moordenaars Karoo (South Africa, 300 km NE from Cape Town), where

a 530 m long stone wall running the full length of the rantjie

reached its summit. The mixed gathering came to witness the Moon

Major Standstill at its rising that would be observable on a

fixed line marked in the veldt by three stone built shrines. I

predicted this event with reference to my research of 27 years in

hundreds of stone structures of this kind all over South Africa

and Zimbabwe. Should it work, as I was sure it would, though not

all of the present observers shared the unequivocal sentiment

with me, the question to answer would be: who, when and for what

purpose built this kind of structures in southern Africa. My

answer was simple: The Quena or Otentottu (commonly known as

Hottentots), who inherited this astronomical knowledge and the

religion that called for it from their Dravida ancestors, who,

searching for gold in Africa miscegenated with the Kung or

Bushman women and produced the Mixed (Otentottu) Quena (Red

People worshipping the Red God of India) owners of pre-European

southern Africa. None of the archaeology departments at South

African Universities was interested. The Moon at its rare and

extreme distance from the sun rose precisely as predicted on the

line of the three stone shrines, which were marked by burning

fires, plus one fire marking the monolith of the true East

shrine. The event was filmed and photographed, and was shown the

following day on ETV as well as in the local newspapers the

following weekend (16Se2011). A feat that has never been

witnessed and recorded on the continent of Africa (ancient

Ethiopia)!

The following Weekend Argus of 23 September 2006, p. 39,

brought a comment from Prof. Andy Smith, the Head of Archaeology

Department at the University of Cape Town, under the title:

“No evidence for India star-gazing heritage: Archaeologist

Andrew Smith challenges interpretation of origins of Karoo stone

walls.” Smith opened his article with: “THE ENTIRE

story of the Indian origins of alignments in the Karoo to

‘read’ lunar events is a complete fabrication by Dr.

Cyril Hromník.”, Weekend Argus, September 16. His

only explanation of these stone walls in the Karoo and elsewhere

was that they “may have been constructed by Khoisan [a

fictitious archaeological name for the genuine Quena] people

defending themselves against Boer expansionism in the 18th

century.”

This paper will present and explain some of the stone temple

structures in the Moordenaars Karoo in their Indo-African

historical context. Cheap Marxist archaeology is no longer

sustainable.

Lange, Dierk

The Assyrian factor in Central

West African history:The reshaping of ancient Near Eastern

traditions in Sub-Saharan Africa

For more than two

decades historians endeavour to reconstruct the past of ancient

Africa in terms of World History but they often do this in

general and speculative frame of mind. They insist on economical

and cultural developments and mostly neglect the formation of

states and dynastic history. The reason for this one-sided

approach to the history of ancient Africa is the supposed dearth

of sources. In fact, traditions of origins as well as oral and

written king lists and chronicles in Arabic contain, if properly

analysed, surprisingly rich material for the reconstruction of

state foundations in sub-Saharan Africa during the pre-Christian

era.

In order to

illustrate the validity of this approach we will concentrate on

the founding of the major states in Central West Africa by

refugees from the collapsed Assyrian Empire towards 600 BCE. On

the basis of recent scholarly work, we will try to show that

these states were established by people belonging to various

communities formerly deported by the Assyrian authorities and

resettled by them in Syria-Palestine. When after the defeat of

the Assyro-Egyptian coalition in 605 BCE, these people were

up-rooted by their aggressive local neighbours, they followed the

Egyptian army in its flight to the Nile valley and they continued

to Central West Africa. Here they must have confronted the local

inhabitants, expelling some and subjecting others. Unfortunately,

the traditions are too vague on these encounters between the

foreign invaders and the autochthones to allow firm conclusions.

The evidence

provided by the dynastic traditions of Kanem-Bornu, the Hausa and

Yoruba states is more precise with respect to the different

ancient Near Eastern groups participating in state-building

process. Contrary to what might have been expected, the members

of the Assyrian elite were largely excluded from the leading

positions in the new states. In their stead the available

dynastic sources in the different states bear witness to strong

reactions against them. In the traditions of the individual

states these early antagonisms are expressed in different terms:

in Kanem tradition by the Babylonian-led Duguwa opposition

against Sefuwa domination, in Hausa tradition by the rise of the

proto-Israelite followers of Magajiya and the marginalization of

Bayajidda and in Yoruba tradition by the Babylonian-led revolt of

Abiodun against the tyrannical Gaha. In all these cases ancient

Near Eastern traditions were profoundly reshaped in accordance

with the fierce opposition of the people against any restoration

of an oppressive Assyrian state on African soil.

Other aspects of

anti-Assyrian attitudes in Central West Africa are reflected in

the rise of states in which the kings were systematically

deprived of effective power and in which queen mothers and queen

sisters were instead given considerable responsibilities. In

conjunction with state-building, ancient Near Eastern influences

can also be suspected in other dimensions of social complexity:

the spread of metal-working and other handicrafts, urbanization,

intensive agriculture, well-digging and even the proliferation of

slavery. In view of the considerable impact of the Assyrian

factor on sub-Saharan history, it is quite conceivable that even

the great Bantu expansion was a distant consequence of the

upheavals produced by the Near Eastern invaders in Central West

Africa towards 600 BCE.

Li Anshan

Contact between China and Africa

before Da Gama: Historiography and Evidence

This is a study

of the history of long contact and cultural exchange between

China and Africa during the pre-modern time. The article will be

divided into three parts. The first part deals with the

historiography of Chinese literature regarding the transnational

and trans-continental activities, including the Chinese classics,

such as the ancient official historical documents as called

“24 Histories”, the non-official historical studies,

and the study by the modern Chinese scholars. The second part

will cover the historical evidence including the archeological

discovery in China and Africa, the data and interpretation of the

cultural contact between China and Africa in early time, and the

summary of the historical study by scholars worldwide. As some

Chinese scholars indicate, the early exchange of commodities

occurred in pre-Han Dynasty while the archeological discovery in

Egypt indicates that such contact may occur as early as the the

1000s before Christ. The third part illustrates the possible

resource of the future study, which might provide more sources of

the historical study of China-Africa relations in the ancient

time.

Njoku, Ndu Life

Africa's Development in the Minds

of Her Children in the Diaspora: Aspects of Diaspora Social

Impact on Africa

Ndu Life Njoku, Ph.D

Department of History/International Studies

Faculty of

Humanities

Imo State

University

Owerri, Nigeria

In the context of

anti-imperialism and area studies, colonial and post-colonial

African cultural and development experience have benefited

tremendously from a popular aspect of African diaspora education

and culture, namely: the intellectual consciousness aroused by

academic discourses on Africa. Through the "expository"

and radical works of scholars and writers like W.E.B Dubbois,

Marcus Garvey, C.L.R. James, George Padmore, Malcolm X, Frantz

Fanon, Walter Rodney, to mention just these, disciplinary

approaches have crystallized and have been adopted to enable each

discipline identify its relevance to the theme of development,

and from the perspective of that discipline propose ideas, offer

new visions, and make meaningful contributions to social develop-

ment thinking in/on Africa. This paper investigates the depth and

relevance of this strong cultural impact

from across the Atlantic. The paper shows that, in both the

short and long terms, varying degrees of not just literary but

also socio-cultural benefits are accruable to the African

experience from the "African-African diaspora intellectual

multi-nationalism" that underlies the African experience.

But, more importantly, the paper asks whether the social and

intellectual climate in Africa today makes for an enabling

environment which would continue to animate and sustain the

Pan-Africanist intellectual cooperation, and make for a

revival and re-invigoration of the fading concern for

Africa's development in a rapidly globalizing world.

Osha, Sanya

Interrogating Afrikology?

Tshwane

University of Technology,

South Africa

African

discourses on Egyptology are becoming more and more established

and they often seek to counter the common Eurocentric bias that

Africa had no history or culture worth talking about. African

scholars of Egyptology in addition to some North Atlantic

intellectuals are now claiming that Africa is in fact the Cradle

of Humanity and hence the foremost vehicle of civilisation.

Increasingly, research is deepening in this respect. But Dani

Nabudere, an eminent Ugandan scholar is taking the project even

further. Rather than stop with the task of proving the primacy of

the Egyptian past and its numerous cultural and scientific

achievements, Nabudere is strenuously attempting to connect that

illustrious past with the African present. This, remarkably, is

what makes his project worthy of careful attention. And this is

essentially what his philosophy of Afrikology is about; tracing

the historical, cultural, scientific and social links between the

Cradle of Humankind and the contemporary world with a view to

healing the seismic severances occasioned by violence, false

thinking, war, loss and dispossession in order to accomplish an

epistemological and psychic sense of wholeness for African

collective self. Of course, this proposition has considerable

importance as a philosophy of universalism and not just as an

African project. Afrikology intends to transcend the dichotomies

of inherited from Western epistemology that maintains a divide

between mind and body or heart and mind and revert back instead

to an earlier cosmology perfected in ancient Egypt that conceives

of knowledge generation as a holistic enterprise where the

fundamental binarisms of the Western universe do not really

apply.

This paper

interrogates the viability of Afrikology as both a philosophy of

action and consciousness.

Oum Ndigi, Pierre

Le dieu égyptien Aker, le dieu

romain Janus et le paradoxe d’une histoire préhistorique de

l’Afrique subsaharienne

HDR, Egyptologue,

linguiste et politologue

Université de

Yaoundé I / Cameroun

De

l’histoire comme « Janus de la vie moderne »

(J . Capart, 1945 : 15), donc continuité entre le

passé et l’avenir, à l’histoire conçue comme rupture

entre un passé qui ignore l’écriture et un passé qui en

procède, il y a toute une différence de conception qui soulève

la question de la pertinence épistémologique d’une

histoire paradoxalement appelée préhistoire .

Dans le cas de

l’Afrique, il y a lieu d’admettre avec certains auteurs

que l’étude de sa préhistoire est absolument indispensable

à la compréhension de son histoire, d’autant plus que

c’est dans celle-là, en particulier dans la connaissance du

Sahara « humide » néolithique que se trouve la clef

de la naissance de la civilisation égyptienne et en même temps

celle de l’unité culturelle du monde noir (R. et M.

Cornevin, 1970 : 6).

A cet égard,

l’égyptologie apparaît aujourd’hui, de plus en plus,

comme une source majeure et primordiale de la nouvelle

historiographie africaine inaugurée par le déchiffrement des

hiéroglyphes en 1822 par J.’F. Champollion, de par la

diversité, l’originalité et l’abondance de sa

documentation.

Dans le cadre de

l’étude des rapports réels ou supposés que l’Afrique

semble avoir entretenus avec d’autres continents dans un

passé reculé dit préhistorique ou protohistorique,

l’objet de notre communication s’inscrit dans une

démarche qui consiste à réfléchir sur l’éclairage que

peuvent apporter certaines sources mythologiques, iconographiques

et linguistiques dans l’intelligence de l’histoire

africaine dont les époques les plus reculées sont évoquées en

égyptien ancien par des expressions caractéristiques telles

que »le temps du dieu », « depuis le temps de

Rê », « les années de Geb – ou Koba, le dieu

du Temps, équivalent du grec Chronos (Oum Ndigi, 1996,

1997 : 383) – que l’on retrouve dans certaines

langues bantu (basaa, duala, ewondo) : Koba

« autrefois », « temps anciens » ;

ndee Koba « temps de Koba » ou « temps

anciens » ; mbok Koba « monde ancien »

(Oum Ndigi,2009 : 20-21

C’est ainsi

que le dieu égyptien Aker, le dieu romain Janus et le dieu

nubien Apedemak, en tant que représentations symboliques de la

double face de l’histoire, font partie de l’imaginaire

des Bantu comme le révèlent leur art, d’un côté, et

certaines de leurs désignations temporelles, en

l’occurrence, akiri et yani signifiant à la fois

« hier » et « demain ». Autant

d’éléments suggestifs qui semblent consacrer

l’universalité d’une conception de l’histoire

comme projection d’un même esprit, l’Être-Temps, à

la fois dans le passé et dans le futur, comparable au dieu

Yahvé des Hébreux ou de la Bible, l’Omniscient, qui se

définit comme étant l’Alpha et l’Oméga, et dont une

expression caractéristique basaa du Cameroun rend compte de

manière inattendue.

Rowlands, Mike

Abstract: Rethinking Civilisation as

Cosmocracies in African and Eurasian interactions

In the paper I will follow Wim van

Binsbergens' recent discussions of the nature of large scale and

long term interactions and connectivities in African prehistory.

First I will summarise some of the most recent archaeological

evidence for long-term interractions between Africa and Eurasia

in terms of exchanges and movements of crops and food

technologies over last four thousand years. Second I will suggest

that a theorising of civilisation by Mauss provides us with a

more flexible framework within which some of the aspects of

regional flows and connectivites and long term continuities can

be understood. Third the suggestion that boundaries between

'house cultures' and 'body cultures' as cosmocracies sustain both

interactions and connectivites between Africa and Eurasia but

also suggest the presence of long-term 'civilisational'

identities’.

Tauchmann, Kurt

Abstract: Transcontinental

continuities around the Indian Ocean during the last 3 millennia.

Space

and maritime context. Forces of marin orientation and maritime

migration. Terrestric and maritime lifestyles. Sedentarisation

and terrestrism. Mobility as historical stigma. Present division

between Land and sea resulted from the last ice age around 10.000

years ago.

Political

leadership in Southeastasian societies was not bound to territory

and had moving centres with occasional reunion of people (

amphictyonia ). Rounding up people and concentrating them in a

certain place within systemic clientelism. Resistance to

oppression resulted in ikut

strategy or flight. Far away „colonies“ were won for

the many princes (Vak)

within polygyny of kings. Economy of plunder, whereby furage was

used to increase and satisfy the clientel. Maritime migrations

were manyfold and did not be a one way afair. North-South and

West-East migrations through the Indian Ocean. Out off and into

Africa, Europa, India, Indochina and Australia. Indian

Ocean culture and society established as a continuum between

three continents. Chinese cultural objects were transmitted into

Africa, Europe and vice versa from Africa and Europe to the Far

East. The central role of Same/ Bajo/ Bugis.

The Cham of Lin-ye and

Funan in present Vietnam, the Iban

and Ngaju in present

Borneo/Kalimantan and the Segeju/Bajun

of Eastafrica. The monsuns and appropriate technical innovations

for sailing and crossing oceans. The emergence of the Malay world

and expansion of the Austronesian group of languages eastwards up

to the Southamerican coast, southwards to Northwest Australia (

Melville Island and Carpentaria Bay ) and Northwards up to Taiwan

and Japan (Okinawa). The space of dibawah

and diatas angin and

Malay as lingua franca in the harbours around the Indian Ocean

until the eight century. Traces of Same/Bajo

serpentines from East and Westafrica up to the Indonesian

Archipelag, Taiwan and Japan. The „masters of the

mountains“ in Nordostafrika and the Federation of

Sungaya. The Etymon Somal, Boran

and Pokomo (Oromo) and

the Galla Phratry

represent the Austronesian category of serpentines (dragons) and

demonstrates Austronesian space categories related to

status. The Shaka appear

as „red“ kings in Northeast-Afrika down to the Zulu

of Southeastafrika and the Sakalava

and Anteisaka of

Madagaskar. Malays appear as Kalanga in Mocambique. The colour

„white“ is not a somatic but a ideological category

since the serpentine (dragon) is symbolised by the milky way and

in Hindu/Buddha context denotes within the varna

category ritual purity of the Brachman elite against the impure

„blacks“, like traders, even one finds some

Brachman’s within international trade in early times, and

„red“ characterizes the habit category of the warrior

class among the Indo-arians. This proofs that colours are not

somatic categories, but ideological ones out of varna

und guna

classifications.

We can

now trace ethnic similaritis between the Somali

of Northeastafrika and the Samal

of the Central-Philippines, the Temuru

as foreigners arriving in Eastafrica und the Anteimoro.

Among the migration legends of the Anteimoro,

who start at the Mekkan sands, is one place, called Ussu, which

also is the toponym of origin of the Bajo-Bugis

at the bay of Bone in the island of Sulawesi/Indonesia. The

toponyms Bédjaya (Vidjaya) und Bugia in Nordafrika and their

economy of plunder directed up to South Italy demonstrate former

Austronesian identity. In Kiwayu and Shanga in the Lamu area of

present Kenya we found traces of remote pre-Islamic

and pre-Bantu

Austronesian context which can answer the question of a

speculative pre-Bantu language niveau in that area. The Etymon Wadebuli

and Wadubuki in Songo

Menara near Kilwa refer to Austronesian space and status

categories. In Swahili Madagaskar

is called Buki, and the

Etymon Buques and Ubuque,

as their language, stand as names of reference for Madagaskar

before the Cazi’s

arrived and confirm with the Eastcoast of Sulawesi/ Indonesia

from where the traces moved towards the Straits of Malacca, the

Indian Ocean South of Sri Lanka, the Maledives, the Comoro

Archipelago or the island of Reunion to Eastafrica or Madagaskar.

The Wak-Wak armadas

mentioned during the 10th century in East African waters as

arrivals from the Far East had their local base on Comoro islands

from where they plundered Islamic trading cities along the East

African coast. Beginning in the 13.Century traces of Austronesian

people at the coast of Eastafrica disappear and can be found

later only around Lake Nyassa in the Hinterland, around the Niger

in Westafrica and in Madagaskar. At the same time migrations into

the Indonesian Archipelago prevail and transmit African cultural

heritage.

(due to

serious illness Prof. Tauchmann will not be able to attend the

conference; in addition to the above abstract, Wim van Binsbergen

will use the present slot in the programme to report on 'the

Oppenheimer-Tauchmann hypothesis of extensive South and South

East Asian impact on sub-Saharan Africa in protohistorical

times´)

Wim van

Binsbergen: A note on the Oppenheimer-Tauchmann thesis on

extensive South and South East Asian demographic and cultural

impact on sub-Saharan African in pre- and protohistory

Thornton, Robert

Glass Beads and Bungoma: The link

between southern India and southern African traditional knowledge

known as bungoma

Anthropology Department, School of

Social Sciences & Chair, Wits University / Human Sciences

Ethics Committee (Non-Medical), University of the Witwatersrand,

Johannesburg, South Africa

The paper examines possible links between the southern African

practices of ‘traditional healing’ (known as

‘bungoma’ as practiced by initiated practitioners

called sangoma) and trance and healing in southern India. The

paper is based on archaeological evidence and artefacts in

southern Africa (Botswana, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Mozambique)

and southern India, and on new archaeological analysis of these

materials, especially the material culture associated with this.

It also utilizes a reading of South Indian iconography, but is

not primarily based on historical reading of texts or oral

evidence. Evidence for an early link—perhaps dating from 600

CE to 1600 CE—is developed by comparing instances of

material culture from traditions of the sangoma in the southern

Africa and the iconography of southern India, especially of

Ganesha and Hanuman. In particular, the ritual use of metal tools

and glass objects, specifically beads (ubuhlalu, insimbi, made of

metal and glass), the ‘mace’ (sagila), ‘axe’

(lizhembe), ‘spear’ (umkhonto, sikhali), the knife

(mukwa), and the ‘fly whisk’ (lishoba, made either of

tails of hyaena [impisi] or of blue wildebeest [ngongoni]). All

of these items are found in the ritual practices and iconography

of the sangoma and of iconography and practices of devotees of

Hanuman and Ganesha, among other gods, in south Indian Hinduism.

This material culture, especially the ‘weapons’ of the

southern African sangoma and the south Indian icons and ritual

practices, show strong similarities that suggest more than trade

was involved in early links between the southern Indian region

and the southern African region.

van Beek, Walter

Smithing inAfrica: The enigma

African Studies

Centre, Leiden

A fierce debate

reigns in African archaeology over the origin of iron production

and iron work in Africa. New dates of early iron sites keep

pushing the first dates of iron production farther back in

history, well into the First Millennium BCE, and gradually, the

earliest African dates seem to be approaching the inception of

iron production in the Middle East. Thus, an increasing number of

scholars posits an independent invention of iron smelting on the

old continent itself, and for some good reasons: the rather

sudden appearance of iron smelting in various areas south of the

Sahara at roughly the same time; the sheer diversity of oven

types used in Africa; and finally the fact that the traditional

diffusion routes, such as along the Nile valley, seem have been

discredited. On the other hand, the absence of a preceding bronze

technology still forms a considerable obstacle, as it is hard to

imagine how a full-fledged iron smelting could develop without

that intermediary phase.

This contribution will not try to formulate a definitive position

on this debate, as that has to be solved by new diggings and thus

new findings, especially better dating. I will approach this

problem from an anthropological perspective, and explore the ways

in which the iron smelting and smithing – as two distinct

occupations – have developed into integrated positions

within African societies. Africa-wide, several patterns of smith

integration into the societies can be discerned, ranging from a

fairly business-like arrangement of specialists, to deep

caste-like divisions in society, and from strictly iron

tdechnology to a clustering of specialisations. This pattern of

smith-integration then will be compared to selected examples from

South East Asia and the Middle East, to ascertain whether there

are systematic differences. The guiding notion of this

contribution is that there are indeed structural differences

between the larger regions, and that these differences may shed

some light on the early phases of the adoption of iron.

van Binsbergen, Wim

A. Key note: Rethinking Africa's transcontinental

continuities in pre- and protohistory

ABSTRACT. Why should we study Africa’s transcontinental

continuities, and how could this be a surprising and

counter-paradigmatic topic, more than a century after the

professionalisation of African Studies? Let me introduce this

topic by explaining how I myself came to study Africa’s

transcontinental continuities. My interest here is not to engage

in autobiographical self-indulgence, but to help lay bare the

structures and preconceptions of Africanist research to the

extent to which they determine our view of these transcontinental

continuities. In the process we shall also address the important

issue of why transcontinental continuities were obscured, not

only from the (potentially hegemonic) view of Western scholars

but also from the consciousness of historical actors in Africa

and Asia. After a few methodological considerations, we will end

with the question of what a fuller awareness of transcontinental

continuities brings to Africa, and what it risks to take away

from, Africa -- finally considering the interplay between

empirical regional Area Studies, and Intercultural Philosophy.

B. (main conference paper) The relevance of Buddhism and

Hinduism for the study of Asian-African transcontinental

continuities

ABSTRACT. The argument considers selected aspects of South and

South East Asian culture and history (the kingship, musical

instruments, ceramics and gaming pieces), against the background

of the results (here briefly summarised in Section 2) of the

author’s earlier results into transcontinental continuities

between Asia and Africa in the field of divination and ecstatic

cults. After posing preliminary methodological questions, the

leading framework that emerges is that of a multidirectional

global transcontinental network, such as appears to have

gradually developed since the Neolithic. Having argued the

possibility of Hinduist and Buddhist influences in addition to

the well-acknowledged Islamic ones, the next question discussed

is: what kind of attestations of possibly transcontinental

continuities might we expect to find in sub-Saharan Africa? From

a long list, in addition to divination three themes are

highlighted out as particularly important: ecstatic cults,

kingship, and boat cults. The discussion advances conclusive

evidence for the Hinduist / Buddhist nature of the state complex

centring on Great Zimbabwe, East Central Zimbabwe, as a likely

epicentre for the transmission of South-East-Asian-inspired forms

of kingship and ecstatic cults. A provisional attempt is made at

periodisation of the proposed Hinduist / Buddhist element in

sub-Saharan Africa, and the limitations of transcontinental

borrowing in protohistorical and historical times is argued by

reference to an extensive prehistoric cultural substratum from

which both South East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa are claimed to

have drawn and which becomes manifest, for instance, in the tree

cult. On the basis of future research advocated here, new

insights in transcontinental continuities are to be expected,

that throw new light on the extent to which Africa has always

been part of global cultural history, and should not be

imprisoned in a paradigm that (out of a sympathetic but mistaken

loyalty to African identity and originality) seeks to explain

things African exclusively by reference to Africa.

Note: initially Wim van Binsbergen was scheduled to

present the following argument, a summary of his book of the same

title, which is now nearing completion; however, this would have

been too large a scope for a mere paper, and would have taken us

into a technical philosophical discussion of the Ancient Greek

Presocratics, while the above replacement paper has more

immediate Africanist content.

This

argument seeks to contribute to the study of the global history

of human thought and philosophy. It calls in question the

popular, common perception of the Presocratic philosophers as

having initated Western philosophy, and particularly of

Empedocles as having initated the system of four elements as

immutable and irreducible parallel components of reality. Our

point of departure is the puzzling clan system of the Nkoya

people of South Central Africa, which turns out to evoke a

cosmology of six basic dimensions, each of which consists of a

destructor, something that is being destroyed, and a third,

catalytic agent. This is strongly reminiscent of the East Asian

correlative systems as in the yì jing

cosmological system of changes based on the 64 combinations of

the eight trigrams two taken at a time; and particularly of the

five-element cosmology of Taoism in general, in which the basic

relations between elements are defined as an unending cycle of

transformations by which each element is either destructive or

productive of the next. Further explorations into Ancient Egypt,

India, sub-Saharan Africa and North America suggest, as a Working

Hypothesis, that such a transformative cycle of elements may be

considered a prehistoric substrate, possibly as old as dating

from the Upper Palaeolithic, informing Eurasian, African and

North American cosmologies; but possibly also only as recent as

the Bronze Age, and transmitted transcontinentally in

(proto-)historical times. With this Working Hypothesis we turn to

the Presocratics and especially Empedocles, whose thought is

treated in some detail. Here we find that the transformative and

cyclic aspects of the putative substrate system also occasionally

surface in their work and in that of their commentators

(especially Aristotle and Plato), but only to be censored out in

later, still dominant, hegemonic and Eurocentric interpretations.

This then puts us to a tantalising dilemma: (1) Can we vindicate

our Working Hypothesis and argue that the Presocratics have build

upon, and transformed (as well as misunderstood!), a cosmology

(revolving on the cyclical transformation of elements) that by

their time had already existed for many centuries? Or (2) must we

altogether reject our Working Hypothesis, give up the idea of

very great antiquity and transcontinental distribution of a

transformative element system as an Upper Palaeolithic substrate

of human thought – and in fact revert to a Eurocentric

position, where the attestations of element systems world-wide

are primarily seen as the result of the recent transcontinental

diffusion of Greek thought from the Iron Age onward. Both

solutions will be considered. Typologically, but with

considerable linguistic and comparative mythological support, our

argument identifies essential consecutive steps (from ‘range

semantics’ to binary oppositions to cyclical element

transformations and dialectical triads), in humankind’s

trajectory from Upper Palaeolithic modes of thought towards

modern forms of discursive thought. It is here that the present

argument seeks to make a substantial contribution to the theory

and method of studying the prehistory of modes of thought

worldwide. On the one hand we will present considerable

linguistic arguments for the claim of great antiquity of the most

rudimentary forms of element cosmology. On the other hand, we

will apply linguistic methods to identify the origin, in West

Asia in the Neolithic to Early Bronze Age, not of the postulated

substrate system as a whole but at least of part of the

nomenclature of the Chinese yì jing system.

The region indicated constitutes a likely environment from where

the ‘cross model’ as a mechanism of ‘Pelasgian

expansion’ (van Binsbergen 2010 and in press; van Binsbergen

& Woudhuizen 2011) might allow us to understand subsequent

spread over much of the Old World and part of the New World

– including the presence of the transformative element cycle

among the Nkoya. However, in the penultimate section of the

argument a strong alternative case will be presented: that for

direct, recent demic diffusion from East or South Asia to

sub-Saharan Africa in historical times.

return to: Topicalities page | Shikanda portal index

page last modified: 01-05-2012 18:47:00